🏆 The Triumph of Janet 🏆

How boomer entitlement stole your prosperity

Foundations

There is a peculiar type of young male that haunts the dim, humid corridors of Party Conference. You know the sort. Fresh out of the womb, beclowned in an ill-fitting dinner jacket and sporting a face like a 14” Dominos meat feast. It is, of course, mid-afternoon at the Midland bar.

Imperious yet deeply insecure, these fops are known to have posters of Margaret Thatcher unironically adoring their bedroom wall. This is dress up for young men without an ounce of self-awareness (Payne, 2021). They can recant at length about the minutiae of the glory days of the 1980s as if they were there, and uncritically lionise the Thatcher legacy.

These boys represent the three sigma deviants - the tail end of the cringe distribution. So many of the ingredients are there, but the recipe doesn’t quite work. Like Hyacinth Bucket, aspiration is what drives the affectations, but as she finds, chasing the fantasy with such vigour ensures it remains elusive.

It doesn’t matter that it doesn’t work. Aspiration. That’s why they are playing dress up. Anyone can be anything. They aspire to be someone - to be something. This is one of the core, foundational myths and values of the modern Conservative Party.

These young men are just the caricatures of aspiration. Elsewise, you as a young party member, are to believe in the aspirational principles of ‘free enterprise’, liberty, the triumph of working hard and ‘getting ahead’. All noble ideas.

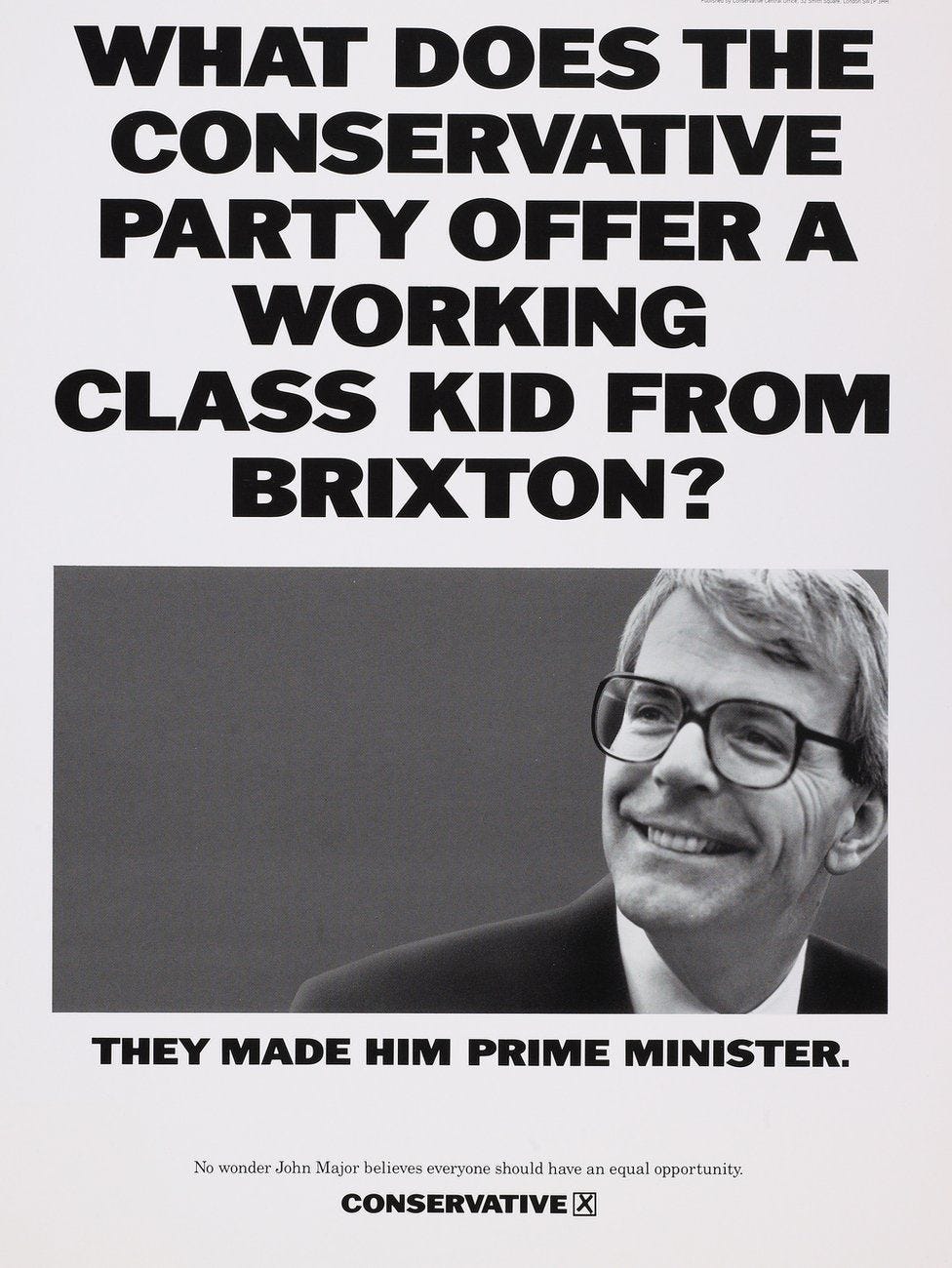

The Conservative and Unionist Party, 1992.

The Conservative Party has, entirely fairly, long held an association with not just aspiration, but privilege, wealth and power.

Thatcher cuts a fascinating figure in this regard, coming from an aspirational lower middle class background, and yet completely cutting through unserious, bloviating, chinless horse-fiddlers to an unrivalled position of ideological and political dominance.

Mission

Central to the Thatcher government’s mission and narrative was a diagnosis of the causes of Britain’s 1970s malaise, set out early in opposition.

Excessively powerful unions lowering industrial productivity. Punitive taxation that suppressed entrepreneurial endeavour. Regulation that went hand-in-hand with nationalised industry, moating incompetence and serving union aristocrats.

The 1979 Conservative manifesto stated:

‘First, by practising the politics of envy and by actively discouraging the creation of wealth, [the Labour Party has] set one group against another in an often bitter struggle to gain a larger share of a weak economy.

‘Second, by enlarging the role of the State and diminishing the role of the individual, they have crippled the enterprise and effort on which a prosperous country with improving social services depends.

‘Third, by heaping privilege without responsibility on the trade unions, Labour have given a minority of extremists the power to abuse individual liberties and to thwart Britain's chances of success,’ (The Conservative and Unionist Party, 1979).

What I think these diagnoses have in common is disdain for deadweight loss - the economic loss borne by society from unfree markets.

More precisely, I read much of this as contempt directed at the accrual of economic rent (any profit that exceeds what is economically or socially necessary to provide a good or service) by those that can set their own industry rules because of their political power, especially if that holds back the greater prosperity of society (Young, 1978).

Rent

An example of economic rent that you may be familiar with is the substantial price differential between private hire vehicles (e.g., Uber) and London black cabs. This price difference is economic rent.

Black cabs - legally ‘Hackney carriages’ - are more heavily regulated, with minimum fare pricing, a requirement to pass ‘The Knowledge’ exam and taxicab design requirements.

But, as has been made clear by the growth of private hire vehicle companies (Department for Transport, 2021), the claimed benefits of the Hackney carriage regulations is not enough for the marginal consumer to pay more for their journey. You are far more likely to go for the low cost option.

However, for a long time, the ability to choose was not in the power of the consumer. Immovable economic rent was accruing to cabbies collecting higher fares, before appification of the booking process for minicabs broke the model.

The mandatory minimum pricing model prevented a market in which the marginal consumer sets a market equilibrium price. I.e., £60 for my journey is too much, but I am willing to pay £55.

This model was unbreakable until a combination of minicab ‘pre-booking’ mobile technology and, arguably, legislatory arbitrage met to offer the choice to the marginal consumer. Otherwise, any attempt at reform would result in strikes that would have crippled the capital’s transport infrastructure. Not something that leads to government popularity.

Strike avoidance and the irreformability of trade union power until the 1984-1985 miners’ strike even resulted in the Heath government’s three day work week - an indication of the scale of union power at the time to shape policy (and maintain economic rents in unproductive industries.)

Supporters of the miners’ strike march down Victoria Street (Sarebi, 1984).

Economic rent can even be accrued in labour markets: Closed shops, which require employees to become and remain a union member as a condition of employment, are another example of the economic rent capture that the Thatcher government sought to discontinue (Young, 1978).

Instead of free, contract-led association, they de facto require you to accept union policy regarding your employment. This can result in economic rent flowing to poorly performing individuals, who may be paid more than they would otherwise achieve in an open shop, or who may be retained longer.

The Thatcher government also divested loss-making state industries, previously sustained by government subsidy. Again, a form of economic rent which required wider society to underwrite unprofitable, heavily unionised industry at a price that it was not voluntarily able to negotiate, under duress from the threat of strike disruption that would make the UK economy unfeasible in the short-medium turn.

Excepting patents, which incentivise invention and creation, there is limited to zero societal benefit to economic rent. The individual able to capture the economic rent is the beneficiary of the arrangement. Wider society suffers. All of which limits aspirational politics.

Janet

When I look to modern Britain, I see an equivalent of all-powerful, societally damaging unions accruing economic rent.

Instead of the National Union of Miners and Arthur Scargill, I see Janet.

Janet Slimfast is 67. A former civil servant, she lives in her detached 3 bedroom house with her husband, Roy. Roy is an unreconstructed Ronnie Pickering. He hates cyclists, wears transition lenses, and thinks charity begins at home.

Janet is the most powerful person in British politics. Forget Rupert Murdoch. It’s all about [email protected].

They’re planning to build some houses a few minutes away from Janet’s house. Not on her watch. A few minutes will be added onto her (car) journey to the garden centre to buy plastic turf and some lawn ornaments.

So she sets down her glass of Yellow Tail Jammy Red Roo, logs off Farmville and on to the local authority website, and sets out her objections. The new development will not be in keeping with the area. The three story houses will be like skyscrapers among the local two storey houses and bungalows. It will increase traffic to unsustainable levels. It will block cherished views of a carpet warehouse.

Janet is dangerous. Not because she doesn’t want this particular development to go ahead, but because she is numerous. She is everywhere. And Janet votes. Councillors fear her. From Truro to Aberdeen, from Anglesey to Lowestoft, there are millions like her.

Does she sound like nobody in particular? If so, fantastic. This is exactly the point I’m making. She isn’t any particular party. Janet is a chameleon. She will not vote for anyone that backs the development and she might just vote for someone that promises to block it.

And if there are millions of her. Nothing will get built.

Incentives

Because all the benefits of blocking development are highly concentrated towards Janet. She doesn’t have to put up with more traffic in her Honda Jazz, pressure on the local GP surgery, dust from construction or changing views. Her house even appreciates in value as the population expands but the number of dwellings does not. Her life is settled and she’s quite happy, thank you very much.

Janet is the beneficiary of these economic rents.

Meanwhile, all the losses from blocked housing development accrue to wider society. This isn’t just expressed in higher housing costs after post-tax income, though the current level is unprecedentedly high in modern Britain.

Young people are paying an unprecedented proportion of their post-tax income on housing costs (Resolution Foundation, 2018).

One second order effect is that higher spending on housing doesn’t result in better quality housing. An indicator of this is declining average floor space per person.

Young professionals being forced to flatshare. Living rooms and offices being converted into bedrooms. Bedrooms being shared by more children. These all make for less pleasant, less human, places in which to live.

The average floor space of younger private renters has declined by around a quarter (Resolution Foundation, 2018).

Another second order effect is the phenomenon of young couples moving out of cities in response to high housing costs, often leaving jobs and careers behind them, in search of an affordable way of having enough space to raise a family.

Seeking more space for their money, parents leave productive jobs behind them (Swinney et al., 2019).

This matters because cities are more productive than towns and rural areas. City size is even correlative with productivity. Ceteris paribus, the bigger the city, the more productive its average worker (Duranton & Puga, 2019).

Large urban conurbations are more productive than their rural and suburban counterparts. And the larger the city, the higher the productivity. (Duranton & Puga, 2019)

So as a society we push fertile age workers (often approaching their peak earning years) away from their current, productive jobs, and create a direct incentive against workers from other regions moving to fill these more productive vacancies via high housing costs, rendering any productivity gains net neutral to income. Any increase in wages is instantly eaten up. So why move?

The outcome? Lower net income, standard of living and quality of life for our worker, and for society: take your pick between higher taxes (because of a less productive society), or worse public services.

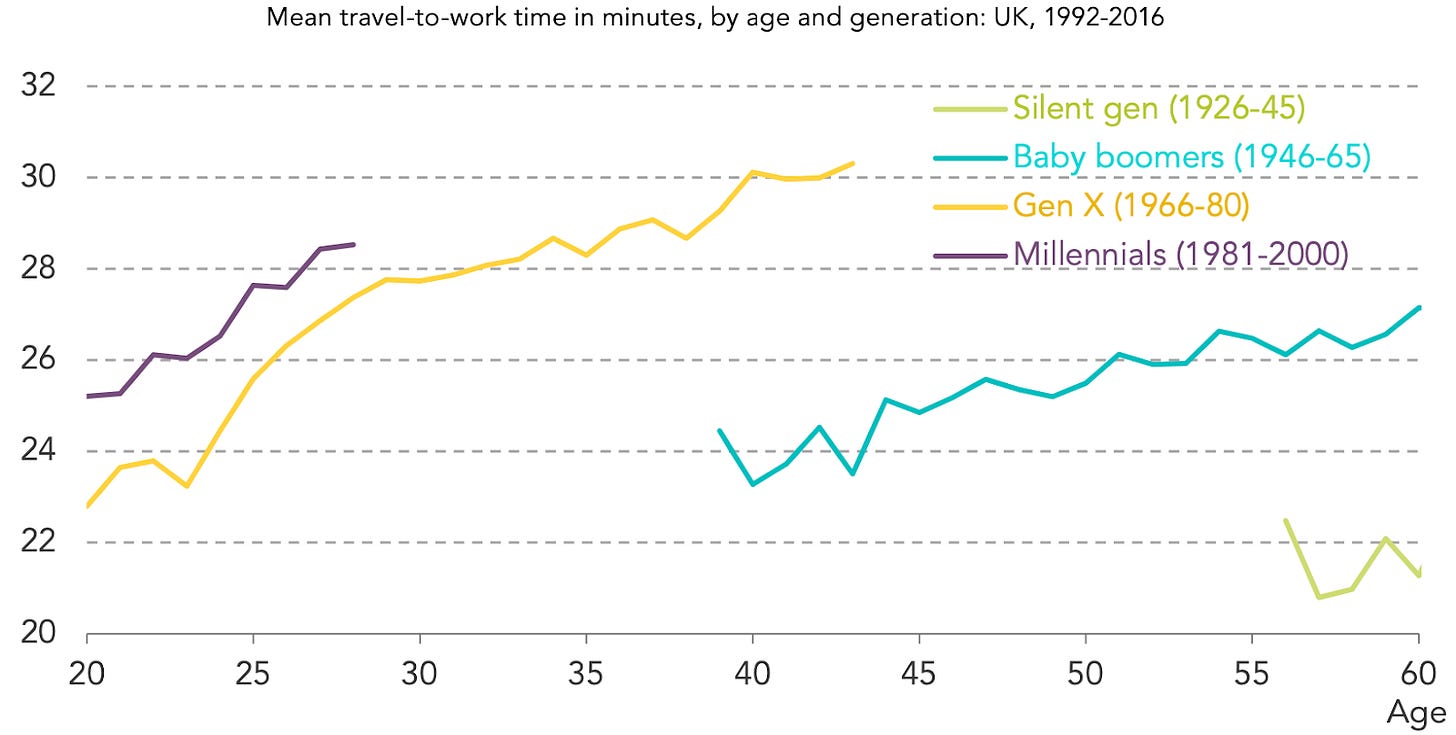

As important as economic productivity is, this is just the surface. As a result of excessively expensive, supply-suppressed housing in our most productive regions, we see lower fertility, longer and more expensive commutes, higher inequality, higher carbon emissions and higher obesity (Bowman et al., 2021).

Higher commute times and living outside of city centres (caused by workers seeking cheaper housing in outer boroughs) is associated with higher emissions (Centre for Cities, 2021) and higher levels of obesity (Christian, 2012, Parise et al., 2021). Chart: (Resolution Foundation, 2018).

This is a disaster. The negative impacts are huge, and they cover virtually every aspect of society. Damage that has been estimated at a quarter of net income (Duranton & Puga, 2019).

The precipitous drop in young adults owning a home in recent cohorts is one of the primary expressions of this damage (Resolution Foundation, 2021).

A common and incorrect assumption is that this crisis of affordability essentially covers London and the south east. In fact, home ownership has fallen across regions - this is a nationwide problem, even if it is most acute in the capital.

While the capital has seen the steepest decline, home ownership among fertile age adults has declined across the United Kingdom (Resolution Foundation, 2018).

But if the impacts are this big, and this negative, why is this the status quo? Simple: because the dispersion and incremental nature of the economic losses involved makes this problem fantastically difficult to dissolve.

Janet is highly and directly incentivised to block the development. The loss of a view or the presence of construction dust is binary and obvious - it either happens or it does not, and Janet notices if it does. The cost of lodging an objection is also extremely low. At worst a couple of wasted afternoons.

But how can young couples assess the incremental benefit of a hypothetical house building in an area they might choose to live in should they be able to save enough for a deposit over 19 years (Resolution Foundation, 2018)? The benefit to these individuals is much harder to personally imagine; it has an incentive so incremental and distant as to be functionally imperceptible.

House-buying and thereby stakeholdership in planning is put out of reach by the time it takes to save for a deposit (Resolution Foundation, 2018).

It is this incremental nature of the impact of housebuilding that leads some (incorrectly) to assume that increasing the supply of housing will not increase affordability in the long run:

‘A low price elasticity – prices not falling by much when supply rises – tells us the exact opposite to there being little unmet demand for more housing. It tells us that there is so much unmet demand, even if we built tens of thousands of new houses, people would still want them so much that prices would stay high.’ (Bowman, 2020).

During a famine, a single bag of flour being delivered to a market will not lower the price of flour. But does that mean you wouldn’t increase the supply of flour?

And we haven’t even yet accounted for Janet’s greater free time as a retiree, rendering her better able to spend time on the solid outcomes of an individual planning objection - rather than juggling the hypothetical and marginal gains of submitting indications of support for various planning proposals with work, childcare and life admin.

Retirees have the greatest amount of leisure time to spend on planning applications (ONS, 2017).

This goes beyond housing, too. Critical national infrastructure is increasingly difficult to build. Proponents of a third runway at Heathrow Airport have been fighting against opponents for decades. HS2 has come under sustained attack. HS3 is effectively cancelled. We haven’t built a water reservoir in decades.

The outcome is a sustained attack on quality of life. Be that in more overcrowded train services. More expensive water bills. Higher carbon emissions. Or higher fares paid to airlines that have to compete for a limited number of higher priced landing slots.

Cohort

Not content with making your standard of living worse via mere prices, climate change and infrastructure, Janet is taxing you more, too.

The UK tax burden, under a fourth term, Conservative-led government, is approaching its highest level since the Second World War.

(Weldon & Canene, 2022).

This has, you might argue, arisen from the combination of three recent economic shocks: the Global Financial Crisis and Great Recession, the economic upheaval of leaving the European Union and Single Market, and the chaos rendered by the Covid-19 pandemic.

True. These factors have had a huge impact on the public finances. But another way of looking at the tax burden is: where does it fall, demographically?

You guessed it. Janet is a net beneficiary.

For example, during the 2017 parliament, net tax and benefit policy changes were directed most negatively at 25-50 year olds. Pensioners? No such impact. In fact, a small net gain.

Bad luck, unless you’re a pensioner. Net changes in family income from policy changes over the 2017 parliament (Resolution Foundation, 2019).

Since 2010, we have seen the triple lock policy implemented on pensions. A rise in the national insurance rate (not paid by those of pensionable age). The emphasis of taxation on income, not wealth. And working age benefit cuts. All of these represent relative gains to Janet.

This is the story of the Cameron government’s austerity: for pensioners, there was none. Even social care, which is funded at local authority level, was protected from local authority cuts, through legal mandation of social care provision.

If that means working age residents suffer to the benefit of pensioners, then so be it.

The impact of post-2010 government policy on income to working vs state pension age families (Resolution Foundation, 2021).

The result of these political choices is that Janet’s post-housing income cost household income exceeds, for the first time in history, that of a working age household.

Working age incomes are now lower than pensionable age incomes (Resolution Foundation, 2019).

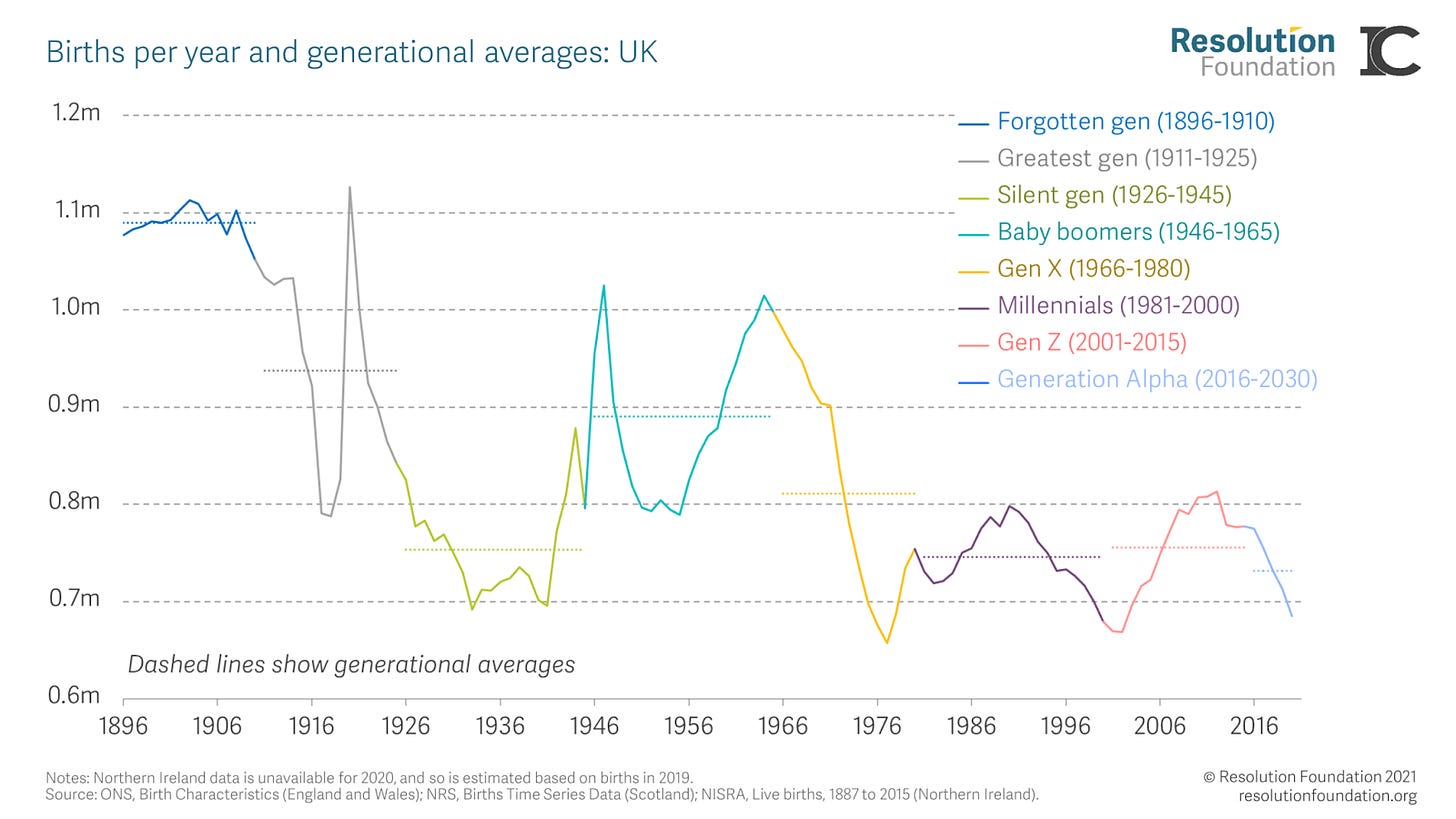

This is the outcome of individuals in a large demographic cohort (they’re called baby boomers for a reason) with similar economic interests voting together. The power to shape the world in your own image.

The baby boomer generation is part of a large cohort, giving greater voting power to the large number of people born in this period, who are likely to have similar spending and policy priorities owing to their similar age, wealth and health conditions (Resolution Foundation, 2021).

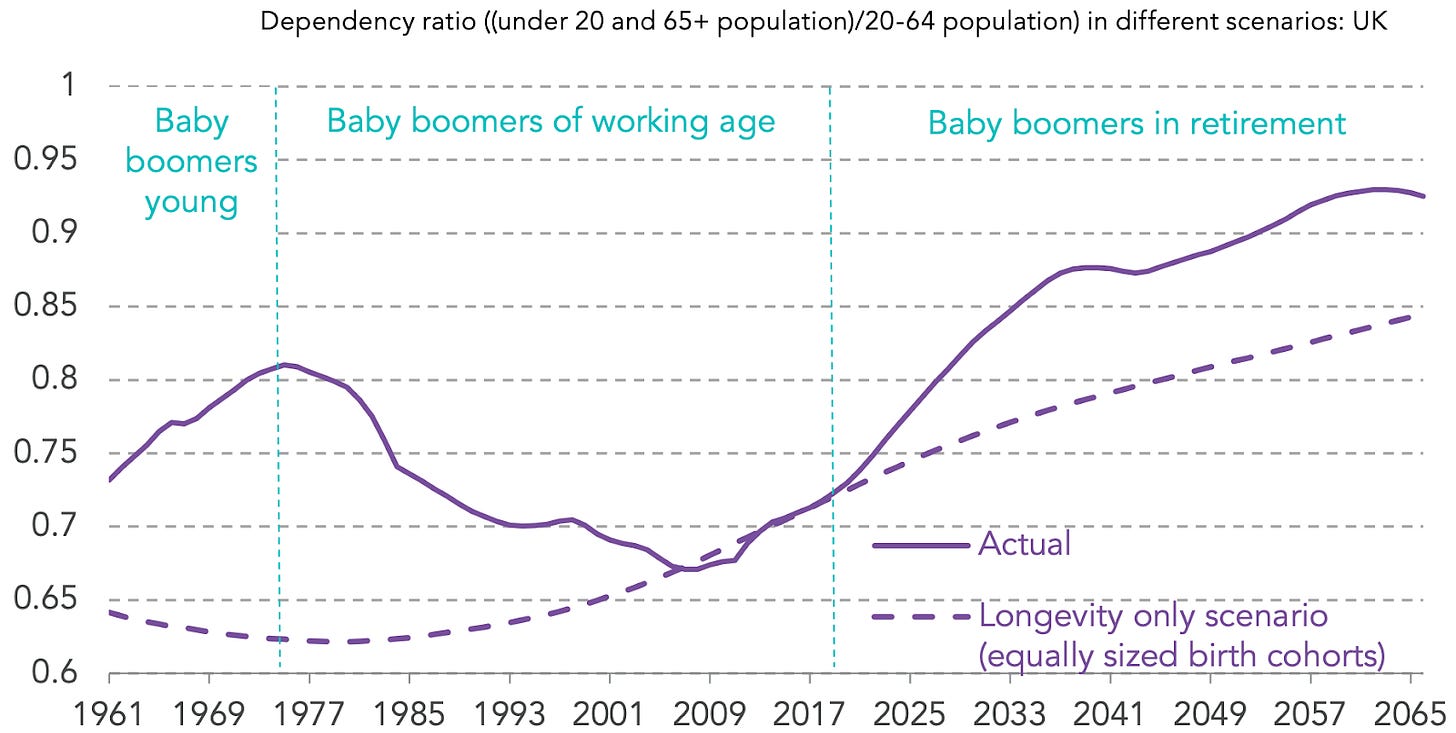

And it’s only going to get worse as the dependency ratio rises. A large cohort of retirees means a large cohort of elderly people to provide pension benefits and health and social care for.

Those retirees are also living longer, stretching out the costs over more years. The treatments required in later years are more complex and expensive, consuming latest generation drugs and equipment.

The number of productive, working age people relative to non productive children and elderly is decreasing, meaning fewer people to fund the non-productive population’s government services and benefits (Resolution Foundation, 2018).

This matters: we cannot expect to be rescued from the costs of a higher dependency ratio through higher fertility. Not if we make raising a family more expensive by raising prices and reducing working age benefits (Driver, 2021). One estimate even suggests 157,000 fewer children have not been born because of the cost of housing (Sabisky, 2017).

Think we’re done yet? Alas, no. Janet will also accrue the once in history generational benefits from defined benefit pension entitlements.

These are not based on your contributions and investments made with those contributions. These are entitlements set to pay out regardless of how well the pension investments perform. Not ideal in our current interest rate and growth environment. Did Janet not pay in enough to fund the entitlements she’s owed by the scheme? Whoops!

But there won’t be a haircut to her entitlement: the young will pay. Not directly, of course. But in the form of lower wages, as the corporate productivity of younger workers is used to plug pension black holes. Those pension schemes, of course, are now closed to new entrants.

We’re still not done. Really. Remember Covid-19? Despite marginal health outcomes for the young, they stayed home to save the lives of the elderly.

Thousands lost jobs. Millions of lives were put on hold. Huge life events like weddings and funerals were cancelled or restricted in number. Schooling and university teaching was axed for months, then implemented in a pale imitation of its former self via video calls. Human social interaction was criminalised.

Little of this was for the personal benefit of the young, who, even in March 2020, were much less likely to be hospitalised or die from Covid. Young compliance with these unprecedented measures was for the selfless protection of the elderly in society, not for the self.

How is this incalculably large societal gift being repaid?

Unintended

The great irony in this is that despite her revealed preferences, Janet doesn’t actually want her grandchildren to have a smaller chance of owning a home or to live poorer lives.

Yes, she doesn’t want construction dust. She doesn’t want the view from the kitchen to change either.

But she doesn’t want her children and grandchildren to be materially poorer because of her voting behaviour. She doesn’t want an unearned entitlement at the expense of anyone that follows in her footsteps.

It hasn’t even occurred to her that she is but one of millions of grains of sand in the machine. This is simply what all our political incentives align to achieve.

Humans will follow incentives that personally benefit them regardless of whether that is good for everyone else. Just ask anyone who has had experience of implementing KPIs in a business.

Someone will always find a way to game the metric. Even if that goes against the business. Even if that goes against the very spirit of the metric. Because what matters is the personal incentive, not the collective outcome.

Planning was never intended to cause these outcomes, either. The original planning bills were enacted to consign the poverty of tenement and slum housing to history. Extending green belts around the larger cities was a product of respect for the rural landscape and its ecology.

It seems shocking today, given the concept of planning permission is so culturally embedded, that planning was only ‘nationalised’ in 1947 by the Town and Country Planning Act of the same year.

Before, the right to build was in the hands of the landowner, not the state. After, development required the expressed permission of the state, and all the stakeholders it chooses to include in the process and listen to.

As information surrounding planning has become easier to access, and objections have become easier to log, the system has jammed up. The utopian structures of the postwar welfare state have been corrupted.

Outcomes

The ultimate outcome of the incentive structures we have created is a gerontocratic Conservative party. The party that pretends to stand for aspiration and growth stands for a society frozen in aspic, like the trout at Janet’s dinner party in 1981.

The elastic of the social contract between the generations is being stretched beyond what is reasonable. The standard explanation for the age split in recent general elections is rooted in social politics: liberal versus conservative social values and Brexit.

While age is strongly correlative with views on Brexit, the phenomenon of an age split in voting pre-dates the 2016 referendum, correlates with all of the political benefits given to the elderly since 2010, an increase in private renting (Singh, 2018), and can be observed in other nation states with similar baby boomer demographics and restrictive planning regimes (Igielnik et al., 2021).

Young people split just as decisively against the Conservative party as older people split decisively for it (YouGov, 2019).

It’s easy to assume that young people have always rejected the Conservative Party. But as recently as 1992, even while much more socially conservative, the Conservative Party took the 18-54 vote by a substantial margin.

The rise of the elderly Conservative vote and the youthful Labour vote is a recent phenomenon (O'Brien, 2019).

Back in 1992, the Conservative Party was not the Boomer Welfare & NIMBY Party. It could claim to stand for the values at the beginning of this essay.

Today, each of the few remaining Conservative voters under 40 should be asking themselves: Should I continue to vote for the party that claims to support my values, or should I vote for my own self interest?

Because what is the point of voting for a party that claims it champions free markets, liberty, and national institutions, if none of these claims are fulfilled, and my personal outcomes are so negative?

Tax rises. Not on the huge housing wealth that the young are locked out of, but on earnings that have barely risen in a decade, and are forecasted to see another decade of stagnation (Resolution Foundation, 2022).

Average real incomes remain suppressed on an unprecedented scale in the postwar period (Jennings, 2022).

What is the point of aspiration when the fruits are so dry and bitter?

Think back to the aspirational caricature we began with. Can anyone be anyone? Not if it takes inherited wealth to get there because you are unable to build your own assets - because of a combination of asset prices, low income and high taxation.

This goes beyond mere equity. The party faces a fight for its survival as the boomer cohort passes on. In the long run, how can a party which stands for the preservation and low taxation of capital survive if later cohorts do not accumulate any capital?

Inheritance won’t save it. The average millennial is set to receive theirs in their mid-sixties - well beyond their fertile years, and well beyond when they might hope to build a foundation for their later life (Institute for Fiscal Studies, 2020). Leaving aside the distributive impact of inheritance (which is essentially untaxed), where the privileged are given a springboard well beyond necessity.

Chipping Barnet is a good example of a parliamentary constituency already at a crossroads. A leafy, north London suburb, it is increasingly being populated by young families priced out from central London, who take their tendency to vote Labour with them.

Think of London as a champagne tower. The more the top coupes fill out, the more champagne flows to the lower glasses. As central London crowds more people into more rooms, subdivides houses into flats and converts living rooms into bedrooms, more and more underhoused people flow to the suburbs.

Chipping Barnet has been a Conservative seat since 1974. Its predecessor seat, Barnet, was Conservative from 1950, and was once held by former Conservative Chancellor and Home Secretary, Reginald Maudling.

In 2019, Theresa Villiers clung on by 1,212 votes. In 2017, her majority was just 353. Young, aspirational voters can see what’s up.

(Redfield and Wilton Strategies, 2022).

The government’s solution? Levelling Up. Under which the areas with the highest housing stress, as indicated by the strong house price signal, are to receive less funding from Homes England, the public body that funds affordable housing in England (Faunce, 2022).

Levelling up? Don’t make me laugh. This is a party that is levelling down its most prosperous areas by choosing not to tackle these productivity drag anchors, while taxing its most productive graduate workers at a marginal rate of over 50% (Eaton et al., 2021).

The abandonment of the Oxford-Cambridge arc project (which would link our two most prestigious university cities with infrastructure, housing and workers) is emblematic of the government’s lack of ambition and active punishment of its most prosperous regions for the sake of government by vibe (Foster & Pickard, 2022).

Levelling up seems little more than planting a few begonias on some provincial roundabouts.

Meanwhile, the Labour Party is nowhere to be seen on these fundamental issues of social and economic justice. Why?

Labour has amassed huge support among young voters in the cities, sometimes achieving highly inefficient majorities of over 50%. It has squeezed this highly geographically concentrated vote for all it is worth.

The size of the boomer cohort is huge, it turns out at elections, and is the core of the current winning coalition. Janet is all that is left to Labour to go after. Thus: political deadlock. Labour must court Janet with even more subsidy to win.

Even beyond the raw and cynical electoral politics, Labour Party activists don’t even focus on equitable housing and childcare costs in rhetoric or activism.

The party of the worker is far more interested in noble but ultimately parochial social and international politics. This is not at all to denigrate the importance of improving transgender rights or seeking peace in the Middle East, for example.

But the energy spent on subjects like these relative to housing and economic growth policy is entirely outsized given the depth and breadth of the damage done to society by the topics discussed here.

To what degree are Britain's minorities benefited by this focus over ensuring housing and childcare remain affordable? It’s even possible to progress on these issues while talking more about other, larger topics.

As for the Liberal Democrats. They would sell their grandmother for a crumb of marginal seat. They are not the friends of anyone under 40.

This is another Corn Laws moment for the Conservative Party. The vested interests in economic rent capture are holding back the country from the much greater, much more equal societal benefits of free market trading. It must choose its supposed own values over its governing revealed preferences.

Onwards

Well, that was fucking depressing, wasn’t it?

You may be familiar with the painting in the background of the image I started this essay with. It is derived from The Triumph of Death, an oil painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, hung in the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

Painted in 1562, it depicts a hellscape that can be said to describe - apt for its age - the crushing, grinding and inescapable inevitability of death (Morley, 2021). It’s easy to see the Janetocracy operating in the same way. She will always win, because everything is tipped in her favour. Her victorious marauding is panoptic, relentless and irrepressible.

And - as tempting as it might be to rectify this by installing tripwires in National Trust homes. To ice pavements outside Costco Wholesale stores. To cut the brakes on every Honda Jazz. To set the satellite navigation on every Mediterranean cruise ship on a one-way, full steam ahead journey to Antarctica.

As much as one might dream about being the host of the first (and last) Annual Landlord Convention. Running full steam ahead against Janet doesn’t work (Payne et al., 2021) - there is simply too much political power in her lobby group because of the size of the baby boomer cohort, and its resultant voting power.

Sometimes sarcasm on the internet feels like all we have left. So, what actions can be taken to address these appalling inequities? I will admit here that I’m not a policy analyst, so what follows are a number of humble suggestions based on my own primary research.

Firstly, as offensive as it may be, given all the other benefits the cohort has amassed, perhaps we must stuff the mouths of boomers with gold, in the form of directly connecting hospital, school and local service development to planning approvals.

Perhaps we must dangle fat, juicy, golden carrots in front of the most privileged, wealthy, entitled generation in history.

While it would be naive to take any polling at face value, dangling carrots in front of voters has the potential to change their policy views (Adam Smith Institute, 2021).

This could be achieved by reclaiming some greater share of planning uplift. Planning uplift is the gain in the price of land when planning permission is granted. Originally, the Town and Country Planning Act 1947 taxed the difference at 100% (Communities and Local Government Select Committee, 2018).

Now, all of that uplift goes to the landowner, unless the local authority implements the voluntary Community Infrastructure Levy or section 106, which on average captures only 25% of uplift value (Centre for Progressive Capitalism, 2018). Given the landowner has contributed nothing to the area or country’s benefit, why is the uplift granted to them?

We should aim to increase the percentage of the benefit of planning uplift to the local authority, allowing campaigning that links development to amenities and services. That said, even this is controversial.

One particularly innovative method of seeking incentives to build that may be less controversial is Street Votes (Policy Exchange, 2021). This would enable individual streets to vote for densification they deem acceptable, such as adding a mansard roof to an existing property.

This has the advantage of allowing for gentle local campaigning in a single street, inclusive of renters (also known as aspirant homeowners), plus potentially allowing a street to vote for its own property values to rise. We know how valuable planning permission is - therefore creating a direct incentive to seek it for a street is likely to result in some densification.

More broadly, reducing the presence and power of the existing stakeholders in planning is also unlikely to pass the political situation unscathed. What may work is the opposite: broadening the stakeholder engagement via further digitisation or appification (potentially including notifications and gamification) of planning. Especially aiming to include young, underhoused people as stakeholders. If only Janet engages, only Janet’s outcomes are taken into account. This cycle must be broken.

We also need to find the language for an intergenerational conversation - one that moves beyond accusations of personal profligacy and fatuous debates over avocado toast. One reason the debate is conducted in this way is the difficulty of making a direct cost of housing comparison across generations.

Most people purchase houses with a mortgage, thus the cost of housing is a function of not just the cost of land acquisition and house construction, but also interest rates and mortgage risk policy. Without the ability to directly compare against earnings, like we can with most consumer products, Janet can only make heuristic judgements.

This also doesn’t account for the gap between perception and reality on prices - most boomers bought their home decades ago. Are they truly aware of what prices are today?

The interest rate peaks in the 1980s and 1990s led to many experiencing a period of negative equity, and for an unlucky few, repossessions and this looms large in the boomer mindset. But, if that was survived, as most managed to, then the lifetime cost of house purchase was much smaller than today.

Mortgage Interest Relief at Source (MIRAS) is also forgotten - a tax arrangement that allowed the interest payments on mortgages to be taken out of pre-marginal tax rate income.

In fact, taking MIRAS, prices and interest costs into account, for the average first time buyer, the real cost of purchasing a first property was much lower before 2000 (Resolution Foundation, 2021).

Research by the Resolution Foundation indicates that far from interest rates being a comparable cost to today’s high prices, the lifetime payments were much lower for previous cohorts (Resolution Foundation, 2021).

Of course, the high interest rates were implemented to counter the higher inflation of the period. Which has the benefit of inflating away debts.

But challenge the narrative that it actually is harder today and the hackles instantly raise, because foundational beliefs are challenged: the argument drawbridge goes up. Too often the conversation turns to ‘I’ve paid in all my life’. The human psychology of loss means taking away any of the perks accumulated by boomers is keenly resisted.

Perhaps we need to ask if they really think young people really have given up on an aspiration that transcends all generations since the war in preference of a bite of avocado toast and flights to Alicante. Is that really realistic? Not even to mention how these ‘luxuries’ are much more affordable than when Boomers were in their 20s.

Speaking of so-called luxury. What happened to building beautiful? If we seek consent from communities to build in and around them the least we might offer them are beautiful homes and streets. Indeed, research finds the public are far more in favour of ‘pastiche’ design aesthetics, while designs favoured by architects featuring cladding and walls of glass, are disliked (Create Streets, 2014).

Preferencing regionalism over localism also appears to be a route forward, as metro mayors seem better able to campaign for a regional vision than local councils and councillors. From campaigning on unified public transport ticketing from Andy Burnham (thereby reducing the oppression of car-choked streets on communities) to Ben Houchen campaigning to keep open Teeside International Airport (increasing regional job and growth opportunities), regional administrations seem to have more strategic, less tactical visions for their jurisdictions.

Finally, there is the potential of introducing a requirement in legislation that the needs of future generations are assessed and contribute towards the political process of developing new laws, as the Wellbeing of Future Generations Bill attempts to do (Wellbeing of Future Generations Bill [HL] - Parliamentary Bills, 2022).

Though it’s worth noting that this approach has attracted criticism on the basis that ‘There is little institutional design to keep the mandated bureaucracy on-target to achieve longtermist goals; in contrast it does seem likely to contribute to the vetocracy that makes effective action so difficult in modern democracies.’ (Myers, 2022).

In the meantime, do what you can: save yourselves with individual actions. Partner early, move in together and cut your rent in half. Vote in your own interest. Invest as early as you can in equities and a pension. And frankly, move abroad.

Acknowledgements

You’ll notice this entire essay is littered with research from the Intergenerational Centre of the Resolution Foundation. I think their research is essential, innovative and revealing, and commend it in the strongest possible terms, along with its erudite and articulate cheerleader, Lord Willetts.

I also thoroughly recommend the research and ideas put forward by Create Streets, Sam Bowman, John Myers, Ben Southwood, Samuel Hughes and Jeremy Driver, each of whom have been instructive guiding lights in the ideological gloom.

References

Adam Smith Institute. (2021, September 24). Build Me Up, Level Up: Popular homebuilding while boosting local communities — Adam Smith Institute. Adam Smith Institute. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.adamsmith.org/research/build-me-up-level-up

Bowman, S. (2020, August 7). It's the supply, stupid - by Sam Bowman - Consumer Surplus. Consumer Surplus | Sam Bowman | Substack. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://sambowman.substack.com/p/its-the-supply-stupid?

Bowman, S., Myers, J., & Southwood, B. (2021, September 14). The housing theory of everything. Works in Progress. Retrieved March 22, 2022, from https://www.worksinprogress.co/issue/the-housing-theory-of-everything/

Centre for Cities. (2021, July). Net zero: decarbonising the city. Centre for Cities. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.centreforcities.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Net-Zero-Decarbonising-the-City.pdf

Centre for Progressive Capitalism. (2018, February). Are current methods, such as the Community Infrastructure Levy, planning obligations, land assembly and compulsory purchase adequate to capture increases in the value of land? Written evidence submitted by the Centre for Progressive Capitalism [LVC 011]. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from http://data.parliament.uk/writtenevidence/committeeevidence.svc/evidencedocument/housing-communities-and-local-government-committee/land-value-capture/written/78481.html

Christian, T. J. (2012, October). Trade-offs between commuting time and health-related activities. PubMed. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22689293/

Communities and Local Government Select Committee. (2018, September 13). Land Value Capture - Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee - House of Commons. Land Value Capture - Housing, Communities and Local Government Committee - House of Commons. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201719/cmselect/cmcomloc/766/76605.htm

The Conservative and Unionist Party. (1979, April 11). Conservative General Election Manifesto, 1979. Margaret Thatcher Foundation. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/110858

Create Streets. (2014, May). Pop up poll results. Pop up poll results. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from http://www.createstreets.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Create-Streets-Pop-up-poll-1.pdf

Department for Transport. (2021, June 30). Taxi and Private Hire Vehicle Statistics: England 2021. GOV.UK. Retrieved March 15, 2022, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/997793/taxi-and-private-hire-vehicle-statistics-2021.pdf

Driver, J. (2021, September 14). Natalism for progressives. Works in Progress. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.worksinprogress.co/issue/natalism-for-progressives/

Duranton, G., & Puga, D. (2019, December). Urban Growth and its Aggregate Implications. National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w26591/w26591.pdf

Eaton, G., Canene, K., & Johnson's, B. (2021, September 8). How the tax system squeezes graduates. New Statesman. Retrieved March 25, 2022, from https://www.newstatesman.com/economy/2021/09/how-the-tax-system-squeezes-graduates

Faunce, L. (2022, February 2). Five takeaways from the UK's levelling-up plan. Financial Times. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.ft.com/content/b33d843a-8755-4ecf-afdc-f9ae000fd184

Foster, P., & Pickard, J. (2022, February 25). Plans to create UK rival to Silicon Valley shelved by Boris Johnson. Financial Times. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://www.ft.com/content/5a9f0603-1404-4f80-a208-f5943d99ff73

Igielnik, R., Keeter, S., & Hartig, H. (2021, June 30). Behind Biden's 2020 Victory. Pew Research Center. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2021/06/30/behind-bidens-2020-victory/

Institute for Fiscal Studies. (2020, July). Inheritances and inequality within generations. Institute for Fiscal Studies. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://ifs.org.uk/uploads/R173-Inheritances-and-inequality-within-generations.pdf

Jennings, W. (2022, April 3). Average real earnings (in 2010 £s). Twitter. Retrieved 4 5, 2022, from

Morley, T. (2021, March 27). The Triumph of Death: A Haunting Portrait That Reveals Humanity's Remarkable Progress. Foundation for Economic Education. Retrieved April 8, 2022, from https://fee.org/articles/the-triumph-of-death-a-haunting-portrait-that-reveals-humanitys-remarkable-progress/

Myers, J. (2022, March 9). Concerns with the Wellbeing of Future Generations Bill - EA Forum. EA Forum. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/TSZHvG7eGdmXCGhgS/concerns-with-the-wellbeing-of-future-generations-bill-1

O'Brien, S. (2019, May 21). The rise of the grey vote | IPR blog. University of Bath Blogs. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://blogs.bath.ac.uk/iprblog/2019/05/21/the-rise-of-the-grey-vote/

ONS. (2017, October 24). Leisure time in the UK: 2015. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/satelliteaccounts/articles/leisuretimeintheuk/2015

Parise, I., Abbott, P., & Trankle, S. (2021, December 31). Drivers to Obesity—A Study of the Association between Time Spent Commuting Daily and Obesity in the Nepean Blue Mountains Area. National Center for Biotechnology Information. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8744747/

Payne, S. (2021, October 9). Tory taste for suits and ties is not for turning. Financial Times. Retrieved March 15, 2022, from https://www.ft.com/content/f3ee48eb-d42f-4d69-8b67-b071e5149aa8

Payne, S., Pickard, J., & Hammond, G. (2021, June 18). Johnson faces backlash on planning reform after by-election blow. Financial Times. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://www.ft.com/content/af9c7bfb-d8d5-4c62-83d7-3a97e3238d65

Policy Exchange. (2021, February 17). Strong Suburbs. Policy Exchange. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://policyexchange.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/Strong-Suburbs.pdf

Redfield and Wilton Strategies. (2022, April 19). Between the Labour Party and the Conservative Party, which do Britons most associate with lower taxes? Twitter. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from

Resolution Foundation. (2018, May 8). A New Generational Contract. Resolution Foundation. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2018/05/A-New-Generational-Contract-Full-PDF.pdf

Resolution Foundation. (2019, March 29). My Generation, Baby: The Politics of Age in Brexit Britain • Resolution Foundation. Resolution Foundation. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/comment/my-generation-baby-the-politics-of-age-in-brexit-britain/

Resolution Foundation. (2021, October 1). An intergenerational audit for the UK. Resolution Foundation. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2021/10/An-intergenerational-audit-for-the-UK_2021.pdf

Resolution Foundation. (2021, October 15). A return to boom and bust (in births). Resolution Foundation. Retrieved April 5, 2022, from https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/a-return-to-boom-and-bust-in-births/

Resolution Foundation. (2022, March 2). Inflation Nation. Resolution Foundation. Retrieved March 25, 2022, from https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2022/03/Inflation-nation.pdf

Sabisky, A. (2017, July 16). Children of When. Squarespace. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56eddde762cd9413e151ac92/t/596b3f33e3df283933d5a5b0/1500200759133/Housing+and+fertility.pdf

Sarebi, N. (1984). Miners' Strike rally, 1984. Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:UK_miners_strike_(1984)#/media/File:Miners_strike_rally_London_1984.jpg

Singh, M. (2018, March 5). Housing Crisis: Renters Are Driving British Voters to Labour. Bloomberg.com. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2018-03-05/housing-crisis-renters-are-driving-british-voters-to-labour

Singh, M. (2018, March 19). Is the rentquake analysis a spurious correlation? - Number Cruncher Politics. Number Cruncher Politics -. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.ncpolitics.uk/2018/03/is-the-rentquake-analysis-a-spurious-correlation/

Swinney, P., Carter, A., & Walker, D. (2019, March 18). London population: Why so many people leave the UK's capital. BBC. Retrieved March 31, 2022, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-47529562#comments

Weldon, D., & Canene, K. (2022, February 9). The rise of high-tax Britain. New Statesman. Retrieved March 25, 2022, from https://www.newstatesman.com/politics/uk-politics/2022/02/the-rise-of-high-tax-britain

Wellbeing of Future Generations Bill [HL] - Parliamentary Bills. (2022, March 8). Parliamentary Bills. Retrieved April 20, 2022, from https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/2869

YouGov. (2019, December 17). How Britain voted in the 2019 general election. YouGov. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2019/12/17/how-britain-voted-2019-general-election

Young, J. (1978, January 31). Radio Interview for BBC Radio 2 Jimmy Young Programme. BBC Radio 2. https://www.margaretthatcher.org/document/103508 /

An excellent analysis from a micro-economic viewpoint. You are quite correct when stating: "Perhaps we must dangle fat, juicy, golden carrots in front of the most privileged, wealthy, entitled generation in history." I am from the last of the Silent Generation and remember the privations of post-war Britain, living as I did in a working class community in the depths of Luton backstreets. I know poverty and being kept in my place.

I rose through the ranks by the vehicle of scholarship funded by the state to reach the sunlit uplands of my profession. I am aware that my generation benefited immensely and disproportionately because of the macroeconomic environment as fossil fuels drove prosperity during the 20th century. All this ended abruptly around 2000 as EROEI (Energy Returned on Energy Invested) turned negative at this tipping point and real GDP has never been positive since - economic growth has ended and this is what you have detected by observing through the wrong end of the telescope and was predicted decades ago if you read the relevant books.

I have written a book about all this and write a weekly 'Letter from Great Britain' charting the decline and fall of Western civilisation and my 'Chapter 13 - The New Emergent Economy' details what will likely face our younger generations and how they might manage in a world changed beyond all measure. It is the end of the consumerist/landfill excesses of oil-fuelled gift that kept giving.

https://www.theburningplatform.com/author/austrian-peter/

But don't take my word for it. Dr Sid Smith (mathematician) has a talk of just one hour explaining the reasoning behind what you are observing, which of course are the effects of the global shift, and the naive belief that politicians and governments can change anything - they can't and never have been able to more than tinker on the edges of our complex adaptive global systems which will go their own natural way. All we can do is adapt, protect and survive:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5WPB2u8EzL8

My new Substack might interest you especially a recent posting about the cold war MAD policies on the 1960s- 70s:

https://austrianpeter.substack.com/p/the-fourth-turning-pits-the-people?token=eyJ1c2VyX2lkIjoyOTUwMzA1MCwicG9zdF9pZCI6NDk3NzM5OTUsIl8iOiIzeUliVSIsImlhdCI6MTY0NjQ2Nzg2NSwiZXhwIjoxNjQ2NDcxNDY1LCJpc3MiOiJwdWItNzYyNzkyIiwic3ViIjoicG9zdC1yZWFjdGlvbiJ9.X1KevQrseJH5GUU9qTgOZ1tdINEr_Bl0VUCLTx2e82o&s=w

Keep writing though, your research is exceptional, I wonder from whence you came to achieve such erudite discourse.

As a note however, a net 745,000 new persons a year to our shores is clearly unsustainable, we would need to build approcimately 600,000 new homes per year every year to meet this demand, no-one is arguing for no immigration , just sustainable levels and a slower pace to keep up with infrastructure.