Artificial lawns: the devil's carpet 👿🌱

Fake perfect is no perfect at all

Janet’s cheeks flushed. Was it the Beefeater Pink Strawberry Gin, or was it brought on by triumph? She’d checked [email protected] just after Strictly Come Dancing finished, and the council had replied. The extension over the garage of number 15 – the family home opposite – cannot go ahead. Excellent. No construction dust, no noise, no change. Just as she likes it.

She got up from her leather sofa, walked to the window, and looked out over to number 15, smiling as her eyes took in her resplendent, newly fitted artificial lawn. It looks fantastic, she thought. No mess, no maintenance, green all year round. Exactly what her and Roy needed to settle down.

Her lip curled. Some foxes, no doubt, had laid some fox eggs on the lawn. Or was it that blasted yappy terrier at number three? They looked like a scattering of chicken nuggets over her formerly pristine outdoor carpet. ‘Roy, could you head outside and pick those up?’ she asked her husband, sweetly.

The Great Outdoors

There’s something about the great outdoors that features heavily in childhood memories, regardless of generation. Perhaps it’s the novelty of a place that isn’t so familiar as the four walls of home. Perhaps it’s the freedom of possibility a late, humid summer afternoon offers. Perhaps it’s sensual - the rough, knowledgeable texture of tree bark, the intoxicating scent of nature’s innumerable perfumes, or the piquant, autumnal taste of a swollen, sour blackberry.

Perhaps it’s also the danger of freedom. The thrill of becoming lost. The risk of a broken arm, falling out of a tree. The keen, angry sting of a brushed nettle bush. The imperfections of nature that cannot offer complete, bubble-wrapped security and comfort. Imperfection is, in fact, perfection.

Perfection seems a much more philosophically complex concept than imperfection. Societies the world over value perfection in craftsmanship, even if that is used to express imperfection. It matters not that Quentin Massys’s Ugly Dutchess depicts a masculine, ugly old woman with thrusting, wrinkled breasts – the painting is rightfully celebrated for its use of complex techniques, its layered messaging, and its profound cultural impact.

The Japanese art of kintsugi, meanwhile, actively embraces imperfection in the history of an object, using gold lacquer not to disguise, but to honour and highlight repairs made after a breakage.

This active focus on the imperfection itself seems to be a recognition of, and submission to, the fact that we live in a complex, natural, entropic world. But, wherever imperfection exists, there is someone out there to sell you the dream. Why submit to the chaotic, beautiful imperfections of nature, when you can have a ‘forever flawless’ artificial lawn?

The Perfection Solution

Advertised by their promoters as the perfect solution to gardens bronzed by the unrelenting warmth of climate change, time spent outside mowing and weeding, burn marks from pet urine, and dirty shoes, the artificial lawn market has expanded rapidly in the last decade. There is money to be made – with industry forecasters predicting that global demand for artificial lawn will reach $7bn by 2025, growing at a CAGR of 6.84% between 2020-2025.

They’re not cheap either – Which? magazine advises that fake lawn is comparatively expensive, especially if landscapers or specialists are employed for its installation, which is important for preventing visible seams, wrinkles and having a properly fitted underlay.

Most artificial grasses come in rolls that are two or four metres wide. Cost-wise, they work out at anything from £10 to £30 per m² (on a par with carpet).

Compared with real turf (which costs up to £6 per m²), fake turf is expensive, but you could still make long-term savings. After all, you won't have to buy and maintain a mower, or buy any lawn feed. You'll also save time, as there will be no more mowing, raking or re-sowing.

You could try laying it yourself, but if you want a perfectly level lawn and a good-quality finish, it’s probably best to employ a local landscaper or an artificial lawn specialist to fit it for you.

Many manufacturers will offer to fit the grass for you, and prices vary depending on the complexity of your garden. The prices quoted for fitting a 50m² area ranged from £1,000 to £2,700 - double the price of the artificial grass alone.

So what is the appeal of artificial grass – why is this such a rapidly expanding industry? Clues are abundant in marketing pitches for the product, citing low maintenance burdens and year-round ‘flawless’ green lawn. This Google advert for www.newlawn.co.uk promises to ‘give your family the perfect, safe and mud-free garden year round.’

Meanwhile, https://www.artificialgrassgb.co.uk offers the ‘perfect grass for kids,’ at only £14.99 per m². This this vision of perfection is frankly, chilling.

Can you imagine any child delighting in the artificial crunch of plastic under their feet over the sensory stimulation of real, natural grass in its resplendent verdancy? The intense fragrance of freshly cut lawn. Building a daisy chain. Placing a buttercup under your friend’s chin to see if they like butter. Getting muddy without regard to the risk of parental disdain. This is what the great outdoors should be about – not running around a whitewashed, dirt-free, sterile desert.

The Desert Problem

And sterile is what artificial lawn gardens are. For the removal of nature goes well beyond the blades of grass. To install outdoor carpet, plastic membranes must be laid down to ensure that plants are unable to take root and grow among the artificial fibres. This means no clover, no buttercups, no daisies. None of the invertebrates and other insects that feed on pollen and decomposing matter. No birds, either – what are they to feed upon in this barren wasteland?

www.perfectgrassltd.co.uk offers this dystopian advice for preventing the simple pleasure of watching birds enjoying a source of food during a long, cold winter: ‘Keep bird feeders well away from your artificial grass. These will only encourage droppings to build up and rodents to dig at the grass below the feeder.’ Grim.

The desert conditions persist below ground too – without a source of grass cuttings and other organic matter breaking down into the soil, detritivores like earthworms are starved too. Instead of decomposing humic matter and aerating the soil, without food, they themselves decompose. And deprived of oxygen by soil compaction and artificial membranes, the conditions underfoot offer forth the foul odours of the anaerobic rot of whatever organic matter remains, often amplified by pet urine, a known problem for artificial grass.

But worry not, the purveyors of perfection have another solution: chemicals. We’re not just talking about vinegar, washing up liquid and detergents, soaking into the groundwater. There are companies out there to sell you the smell of real grass for your fake grass. www.perfectgrassltd.co.uk offers this advice for brushing perfume into your plastic.

If you want your artificial grass to smell like the real thing then add some artificial grass cleaner to it and brush it in. These grass cleaners often contain the chemical compound cis-3-Hexenal. This compound is a colourless liquid that has an intense smell of freshly cut grass. Mixed with other ingredients and bingo – you are able to deliver that freshly cut grass smell.

Has anyone suggested to them having the scent of grass by actually having some real grass? It’s not all heavenly in plastic paradise, either, with the very same www.perfectgrassltd.co.uk advising against using lawn fragrance to mask odours that are inherent to artificial grass.

We don’t recommend using these products to cover up the smell of dog wee for example, as we have found it results in a ‘dog wee grass smell’. It is best used like a perfume; you wouldn’t apply perfume or aftershave without washing first!

The Maintenance Problem

Avoiding maintenance is said to be one of the key advantages of artificial lawns. We have already seen that some maintenance is required to prevent the stench of rotting organic matter and dog urine. But at least you don’t have to march up and down it with a machine, right?

Wrong. Outdoor carpets require vacuuming to remove debris such as leaves, blossom and twigs, if they are to fulfil their promise of perfection. The fibres also require regular agitation to remain firm and upright. Many of the outdoor vacuum cleaners for this purpose even bear a striking resemblance to… a lawnmower. No, that isn’t a joke. See the ‘Lazybrush,’ for sale at Amazon, below.

Even regular brushing and vacuuming in colder, wetter climates will not be enough to prevent the buildup of moss and moulds, which darken the lawn, break down the plastic fibres and end the fake perfection. Again, artificial lawn chemicals can come to the rescue – or, if all else fails, you can pressure wash your plastic grass clean again.

The Climate Problem

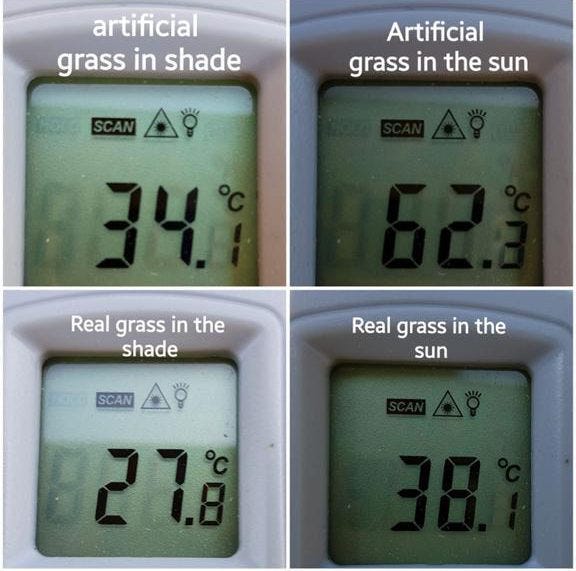

In the summer, moss and mould give way to intense heat, because artificial lawns absorb and radiate much more heat than natural grass. Aura Landscapes tested this with an infrared thermometer, and found that artificial grass in the sun reached over 60ºC – enough to cause thermal burns to human skin.

These artificial lawn temperatures are comparable to metal cars and black asphalt road surfaces, making gardens a less pleasant, usable space – which is, after all, the reason we have gardens. Natural vegetation like tree canopies and grass can instead have surface temperatures up to 12ºC lower than their surrounds, passively cooling cities and providing respite for humans and wildlife during heatwaves.

Many consumers fit artificial lawns to ensure that even during a summer dry spell, their garden remains unnaturally green. The irony of oil-derived plastic lawns intensifying the changes in climate they are often laid down in response to, by absorbing and radiating more heat, is apparently lost on suppliers and buyers.

But prepare yourself for an even bigger question: is parched turf even a problem? Culture is the only reason the British in particular have an obsession with a manicured, green lawn. It’s time we learned to be comfortable with natural variation in plant conditions through the seasons. Grass is astonishingly resilient, too. The photo below of dried-out grass was taken in the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park in mid-August, 2022. Mere weeks later, the rains came, and the grass recovered its vigour and verdancy. Was a few weeks of golden fields really a problem?

The summer of 2022 was an exceptionally dry in the UK – the tenth driest on record since 1836 according to the Met Office. With climate change, extreme weather events such as droughts are going to become more common. Given the heat-intensifying impact of artificial lawns, we either need to get used to bronzed grass in late summer, or start adapting our gardens to become more drought resistant.

The Disposal Problem

So, given how awful artificial lawn is, how easy is it to dispose of it? In fact, artificial lawns dispose of themselves, shedding mass as microplastics into the air and watercourse. Research on microplastic emissions from domestic artificial lawn is limited, but playing field astroturf has been estimated to be the second largest source of microplastics in the environment after road wear and tyre abrasion.

The remainder, once it reaches the end of its useful life of potentially less than ten years, is very hard to recycle, owing to the sheer variety of polymers involved to achieve the ‘right’ texture, ultraviolet light resistance, colour and general durability. Thus, it ends up in landfill.

A report by The Atlantic found that old synthetic turf is already becoming a major landfill problem in the United States.

Hundreds of fields that were installed in the mid-2000s are at or beyond their estimated eight-to-10-year life spans. Now these fields are coming out, en masse. In one 2017 report, the Synthetic Turf Council projected that by the end of the decade, at least 750 fields will be replaced annually.

The average field contains approximately 18 tonnes of plastic carpet and 18 tonnes of infill, according to the report. This means that as much as 150,000 tonnes of waste could require disposal every year.

The problem is not unique to North America – this Dutch-language report (with English subtitles) on how artificial turf is disposed of at the end of its useful life in the Netherlands found that often, recycling facilities do not follow through with their promises – either taking the money and storing the turf instead of recycling it in reasonable time, or even selling it abroad to jurisdictions as diverse as Suriname, Curaçao, Ghana and Mauritania.

It also found that local governments can end up footing the cleanup bill in a game of hot potato, with firms that promise to recycle these materials accumulating mountains of waste, only to declare bankruptcy.

Storing large volumes of flammable plastic and rubber is inherently risky, too. The very same facility featured in the Dutch report later suffered a large fire, which took days to put out, releasing toxic fumes into the air.

The Aesthetic Problem

All of the above said, the most fundamental reason to despise artificial lawns, is that they look shit. Twitter accounts like @Shitlawns are doing God’s work in sharing examples of tacky, lifeless green carpets that far from looking like a perfect lawn, look like what they are – fake, plasticky, and artificial.

This essay began with a love letter to the imperfections of nature, and the beauty of skilled imperfection. Fake lawn companies can add in slightly yellowed or browned plastic blades of grass in an attempt at realism, but they can never truly imitate the perfect imperfection of nature. Outdoor carpet follows the ‘uncanny valley’ model of emotional response to likenesses.

That is to say, it looks unnatural and dystopian precisely because it is so close, and yet so far, from the natural thing it is trying to emulate. Uncanny valley is more than just vibes – it has a real evidence base.

Artificial lawn installation companies often share before and after comparisons that look like the opposite of a Facetune. Before, the perfect imperfection of nature – a garden habitat for invertebrates, hedgehogs, insects and birds. After, a sterile, fake perfection – devoid of variation, devoid of life.

The installation company for this particular example, Neograss, instead claims the family have a new, ‘lush green oasis,’ with ‘clearly defined borders’ – borders presumably to keep the wildlife out.

Weeds, weeds and more weeds! That was what led this homeowner to believe that they were left with no choice but to have artificial grass installed. Since having it done, the customer couldn’t be happier with the end result.

What was once an unpleasant place to spend time has been transformed, and this garden is now a lush green oasis with relaxing seating areas and clearly defined borders. This is vital for this young family and their pets as they love spending as much time as possible out in the garden.

The Cultural Problem

Fake turf is the manifestation of a deep cultural weakness, expressed in short-termism and a distaste and disrespect for the wonder, variety, and temporality of the natural world. Artificial lawns are the Live, laugh, Lobotomy of gardening.

Not everyone has time or inclination to maintain a perfectly manicured lawn. But even holding this as the aspirational standard isn’t right – the most manicured lawn isn’t particularly biodiverse, nor is it particularly supportive of urban and suburban wildlife.

Artificial lawns argue against, rather than running with the grain, of nature. It makes us forget our place in the world. As the dominant, intelligent species, we can be guardians, supporters and guarantors of nature, reducing our outsized footprint and supporting biodiversity. Or we can strim the weeds out of outdoor carpet, not even noticing nature fighting back.

It’s time to go to war against artificial lawns. Some municipalities already are – Boston has banned plastic turf in its city parks, while the aforementioned @Shitlawns account is a fantastic hub for activists looking to end their proliferation.

Professional societies are also weighing in – the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) recently declared: ‘We launched our sustainability strategy last year and fake grass is just not in line with our ethos and views on plastic. We recommend using real grass because of its environmental benefits, which include supporting wildlife, mitigating flooding and cooling the environment.’

The RHS’s flagship event, the Chelsea Flower Show, introduced a ban for fake grass in 2022. Even if we can’t ban it nationwide, surely the civic minded among us can take the initiative in filling watering cans with acetone and paying a visit to our dear neighbours’ artificial lawns? We’d only be doing them a favour.

If that doesn’t take your fancy, do what you can. If you move somewhere with one, or if you have one already – rip it out, and restore the hum, buzz and beauty of nature to your surrounds. The planet will thank you, and so will your discerning neighbours.

Great article. Plastic lawns are an attempt at immortality just like the obsession with stone Victorian houses, "built to last". We should be frequently reminded how quickly nature would reclaim them from us.

And that, for me, is what defines the Janet generation. A refusal to let go, a demand to control the zeitgeist and undermine the young from becoming adults - resisting the natural cycle of youth, life and age in work, politics and nature.