🇬🇧 Britain isn't working 🚧

Our choices have consequences

I want to get straight to the point.

We all know how bad things are: massive debt, social breakdown, political disenchantment. But what I want to talk about today is how good things could be.

Don't get me wrong, I have no illusions. If we win this election, it is going to be tough. There will have to be cutbacks in public spending, and that will be painful. We will need to confront Britain's culture of irresponsibility and that will be hard to take for many people. And we will have to tear down Labour's big government bureaucracy, ripping up its time-wasting, money-draining, responsibility-sapping nonsense.

None of this will be easy. We will be tested. I will be tested. I'm ready for that – and so I believe, are the British people. So yes, there is a steep climb ahead.

But I tell you this. The view from the summit will be worth it.

- David Cameron, in his 2009 speech to Conservative conference

Three strikes and you can’t go out

Nothing seems to be working. Today, 500,000 workers are on strike. I need to think and plan ahead if I want to travel by rail, take a bus, post a letter, travel abroad, or have a driving test. I also need to think about things I can’t plan for, like if I need an ambulance or nursing care if I get sick – which is far too often at the moment as we catch up on what we didn’t get during Covid-19 lockdowns.

Teachers and nurses, professions which straddle the working-middle class divide through status and educational attainment, are joining picket lines too. Even solidly middle class professions are striking, from university lecturers, to doctors, to barristers, who voted to walk out last year over pay and conditions. Poetically, even the Jobcentre isn’t working – Department of Work and Pensions staff were striking over the Christmas period.

Broadcasters and newspapers have taken to providing ‘strike calendars’ to help us plan our lives around disruption.

This isn’t like things were before. Sure, you might expect to see Rail, Maritime and Transport union (RMT) members go on strike fairly regularly, but they’re so predisposed to it, they’re practically French. All Mick ‘Michel’ Lynch was missing during his firebrand TV interviews was a beret, a fag, and a glass of breakfast wine. The current run of prolific but uncoordinated strike action is unusually wide and impactful, compared to recent years.

Before we get ahead of ourselves, it’s important to recognise that working days lost to strikes are a drop in the ocean compared to the disruption seen across the 1970s and 1980s.

But this is not an unbiased comparison – let’s also not forget that this large reduction in days lost to strike action since the 1990s follows the union-busting reforms of Margaret Thatcher, later tightened by David Cameron’s government. The outcome of both these rounds of reforms was to restrict the ability of unions to call strikes by raising turnout thresholds, and increasing conditionality. Trade union membership has also declined precipitously since the 1980s, following the Thatcher reforms, notably even as the population has grown.

It is necessary to ‘rebase’ to the new reality under the new rules – comparisons with the 1970s simply measure the difference in law, not worker conditions and pay. Therefore, if we want an apples-to-apples comparison of ‘worker discomfort’, this chart, showing a big increase in strike action compared to the period after the Cameron reforms, is actually more informative. Strike action is (under these laws) unprecedentedly high, indicating conditions and real pay have materially fallen.

Winter of discount food

Strike action has proliferated so strongly this winter simply because inflation is at its highest for 41 years, squeezing real incomes at the fastest rate in generations. There is also clearly a labour shortage with job vacancies running around a third higher than before Covid, worsening conditions for the limited workforce able to maintain services. These strikes do not appear to be about holding out against reform in unprofitable state enterprises, or moating economic rents; they are about stretched workers and fragile household budgets.

The pound in our pocket is buying 10% less than it would have done a year ago, and we’re noticing. I daresay your eyebrows have raised more than once at the supermarket checkout as your total comes to double what you remember from only a few years ago.

The Consumer Prices Index (CPI) is, of course, an index. Within this index will be differential inflation rates by income level, age, homeownership, number of children and geography, to name a few factors. Then there’s pay. If you are unlucky enough to work in the public sector, your real pay will have fallen even more substantially than wages in the private sector, which have risen more quickly, even if still running behind inflation on average.

Public sector pay at this point has stagnated for more than a decade, and it has declined much more precipitously than in the more flexible private sector employment market in the post-Covid era. Again, that’s average public sector pay — some parts of the public sector have taken the hit more directly than others. The chart below shows the impact on the public sector is highly differentiated by profession.

And while it tracks real term pay growth, it does not take account of working conditions. It would be a stretch to imagine they have improved for most of these groups below, particularly for the otherwise recently better remunerated paramedics. Statistics describing ambulance response times are as grim and upsetting as the human stories behind them.

It’s possible even to go one layer deeper than this, and look at the real changes in pay by seniority across these professions. Much of the fall in public sector wages is being shouldered by senior workers otherwise in their peak earnings years, sustaining a focus on recruitment, rather than retention of skilled, highly productive workers, to plug staffing gaps. For example, the most experienced teachers have seen the biggest pay decline of all teaching staff.

NHS on life support

But nowhere is this more keenly — and obviously and universally felt by the general public — than in the NHS. Pay since 2010 paints the familiar picture of public sector austerity, borne more heavily by higher-earning doctors than nurses, and again, by the most senior doctors.

It is easy to airily brush off the concerns of higher paid consultants, who may be earning more than double the base salaries of foundation doctors, and a few more multiples of the UK median salary. The Daily Express will even prostitute itself out to attacking nurses on just above the UK median salary. The petty troubles of the landed gentry.

But put aside any emotions — the market does not give a flying fuck what you think about social justice — it just is. If the market price isn’t good enough, the marginal supply of labour will reduce, and you need to be prepared to put up with the consequences of that for your righteous vibes.

And the reality is, a decline in relative earnings combined with absurd pension penalties is pushing senior doctors to reduce hours and retire early. Consider the insanity of charging doctors an effective deferred income tax of over 100% for receiving a clinical excellence award, which was charged to ENT consultant Dr Claire Hopkins:

I got a £78,000 charge against my pension for an increase in the annual allowance – and my salary that year was £96,000. In terms of the added value of my merit award over the five years it covered, I was charged more than the value of the award itself.

Hospital doctor data is hard to come by, but there has been a measure and clear decline in GP mean weekly hours worked, facilitated by the — compared to other professions — the easy optionality of working part time by working fewer ‘sessions’ as a salaried GP. We should expect, therefore, that if there is a statistically significant increase in workplace dissatisfaction, average working hours will decrease, and this is what we observe.

Perhaps surprisingly, according to the Nuffield Trust, staff leaving rates across the NHS are broadly flat, if not better than a decade ago, though this analysis does not appear to be on a Full Time Equivalent (FTE) basis, and is not adjusted for increased demographic healthcare demand, which we will need to service with more doctors through some combination of increasing retention and recruitment. Again, hospital doctor data is harder to come by, but the percentage of GPs under fifty with ‘considerable or high’ intentions to leave direct patient care with 5 years has doubled in the last decade.

But that’s nothing compared to the social care sector. Almost half of staff leave their jobs within a year of starting, pushed away by the pressures of the role and the better pay of supermarket and other work. Recruitment is hard too, with the number of vacancies growing by 50% in just one year.

Despite all these pressures on recruitment and retention, much like with the pension penalty, the government also continues to shoot itself in the foot by holding firm on care sector wages and the bonkers policy of capping medical student numbers. The gap, made worse by many British doctors leaving for the better pay and conditions of the Antipodes, is met by importing doctors from overseas, which runs against the government’s own policy objectives on migration numbers.

Luckily, government ministers can fall back during interviews on pay being set by the 'independent pay review bodies’. These ‘independent’ pay review bodies must consider departmental spending envelopes and the government’s inflation target before giving the government their advice on remuneration, rather than purely considering organisational goals, staff retention and recruitment goals, and regional variations in area desirability and cost of living. It’s perhaps a cheap shot, but these considerations are not required by IPSA, the body that advises on the pay of MPs.

It’s hard to disagree with Pat Cullen, the General Secretary of the Royal College of Nursing, even if her comments on the process are a touch too conspiratorially cynical for my taste:

[The independent pay review body is] set up by government, paid by government, appointed by government and the parameters of the review are set by government. So there’s nothing independent about it, and that’s why they came up with the 3% that they’ve come up with. There’s nothing independent about the independent pay review body.

And with NHS outcomes standing where they are, we simply cannot afford to have stupid and counterproductive incentives in NHS staffing. Take 12 hour A&E waits, which have ballooned since Covid.

This is leading to knock on increases in ambulance wait times, with paramedics left waiting outside hospitals, unable to discharge their patients. Much like how poor wages in the social care sector result in ‘blocked beds’ with hospitals unable to discharge patients back into the community, this is how inefficiencies beget inefficiencies, which beget inefficiencies.

What concerns me most about charts like this, is that I had always assumed the threat of ‘collapse’ in the health service was hyperbole — an understandable but flawed rhetorical device to drive NHS funding up the news agenda by self-interested parties.

While rhetoric may remain the primary function of this argument, it may be more prophetic than its proponents realise. When crisis proliferates and becomes the norm, usually efficient processes can break down in a negative feedback loop. Negative feedback loops do not necessarily scale linearly; they are more likely to scale geometrically, or even exponentially. As described by Ernest Hemingway in his 1926 novel The Sun Also Rises:

“How did you go bankrupt?” Bill asked.

“Two ways,” Mike said. “Gradually and then suddenly.”

One can picture one of the ways in which this really starts to matter over time with a simple demand and capacity chart. Even if capacity rises over time — as it is in the NHS — if the area that rises above the capacity threshold continuously increases, while the recovery time shrinks, the beyond capacity load begins to build up, stressing regular systems.

A system with no recovery time, for instance, is likely to lead to stressed staff taking more (entirely justified) sick leave, further stressing the system for those that remain on the wards. Perhaps a doctor or nurse that stayed beyond handover time, out of commitment to their colleagues and institutional pride, now checks out on the bell. A system on the edge quickly loses its institutional ‘soft’ efficiencies. This point on the non-linearity of stressed systems was thoughtfully covered by Sam Freedman and one of his readers in one of his recent Substack posts on the NHS.

A strained healthcare system can result in knock-on impacts on health, all of which negatively reinforce for other health outcomes and productivity. A delayed hip operation, for example, is likely to lead to reduced mobility, lower cardiovascular health, higher obesity and a reduced ability to socialise and work.

A familiar refrain from the right is that we are simply sending good cash after bad by trying to fix the NHS as an institution. ‘The policy of throwing money at it has been tested to destruction,’ as Christopher Snowdon recently put it.

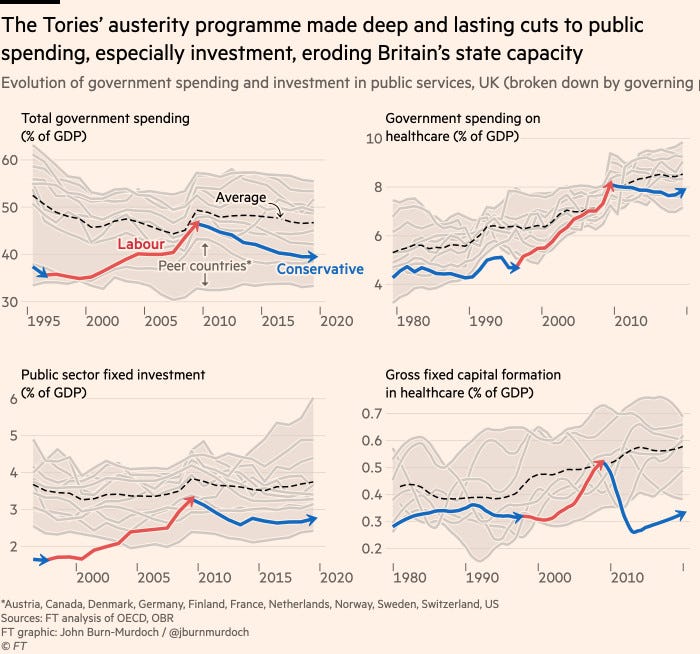

I’m not at all convinced this theory holds however — it seems more likely that the reason the system is struggling is precisely because it hasn’t had enough money. Particularly because spending as a proportion of GDP — especially in terms of capital expenditure — has been consistently low over a sustained period compared to peer nations.

Honestly, structural reform of the NHS that approaches a socialised insurance system — more common to the continent — is irrelevant compared to cold, hard cash. As we found out under the Lansley reform programme, structural reform can be an even greater source of inefficiency than leaving things well enough alone in the short run. As Sam said in his aforementioned post:

Trying to do this in a crisis environment is impossible. It’s inevitable that all resources available are going to get sucked into trying to deal with the massive problems within hospital trusts. There is just no getting around the need for a very large upfront investment in the system to get short term control and create the space for the more substantive reform.

It isn’t clear though whether any party will be prepared to make such an investment — or even what would be required — to create that space. Or whether it can be done politically in the absence of economic growth in a system reliant on general taxation. And the longer we leave it, the more will be needed to salvage the situation.

Maybe we need to have a funding model discussion at some point. Maybe structural reform might unlock some efficiencies and deliver better patient care. This is not even what international comparisons actually suggest, regardless of what vibes-based think tanks and commentators might confidently posit. But if we’re ever going to do this, it would be better do this when the system is under less stress, because funding and structural reform right now could push British healthcare over the edge.

We’ve got no money

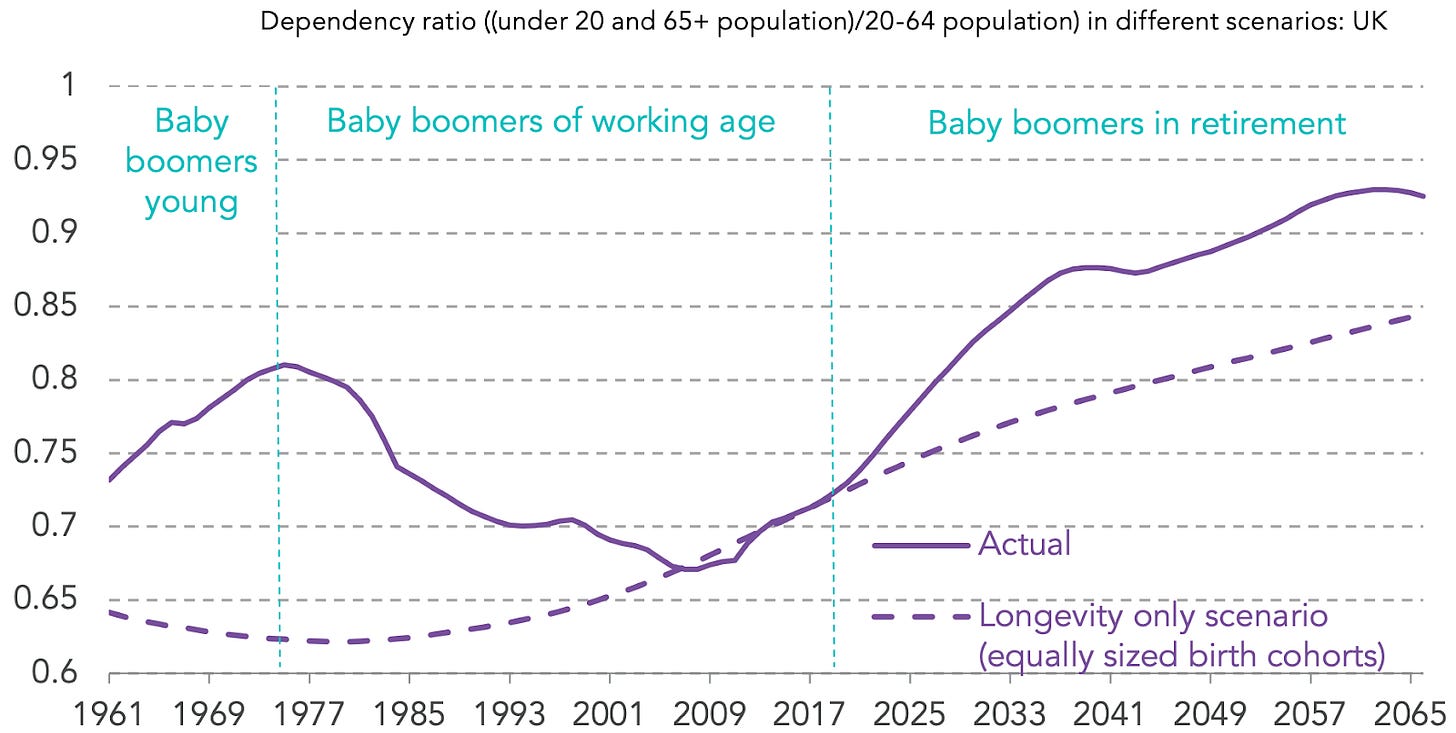

Things are unlikely to get better in the short-to-medium term. The baby boomer cohort is retiring into old age and their health conditions are growing in complexity and cost, which the NHS will need to meet. Their care requirements will be greater than any generation before them — partially because of the sheer number of people in such a large cohort entering old age, partially because life expectancy has risen so much, and partially because diseases and conditions of old age such as frailty and dementia require high contact time, low productivity care.

Some of this too will be ethically immune to productivity improvements. Robosurgery, the development of more complex, complex to mass produce and targeted drugs like biologics, and the diagnostic power of artificial intelligence-enhanced radiology might be able to increase productivity in other areas of healthcare, raising overall worker productivity by preventing and curing sickness.

But denying the elderly human-led social care is clearly a non-starter on mental health grounds, no matter how well shiny, multifunctional and impressive the Dyson ArseWipe 9000 arrives out of the factory. People, fundamentally, like to be cared for in their vulnerable moments by the empathy of human contact, and denying them this would be an affront to human dignity.

These pressures make it all the more challenging to guide a large demographic bulge through the healthcare system, supported by the proportionally smaller tax base and labour force of fewer workers relative to dependents. Since the seventies we’ve been shielded from the negative impact of bad policy by a growing population and a falling dependency ratio, with more workers’ taxed productivity servicing the obligations of society to its young and elderly, like education, old age pensions and emergency care.

But politics can no longer rely on this Get Out Of Jail Free card to solve its problems — certainly after two decades of negligible productivity growth and stagnant wages. We are not used to needing to chase growth. Before, it just happened, like gravity. And growth performed miracles for us: it raised living standards, brought the poor out of poverty, gave us more leisure time and better public services. It made our lives fundamentally better.

It’s hard to emphasise how catastrophically bad British productivity growth has been since the financial crisis. The march of progress, sustained even during the industrial strife of the 1970s, running essentially unbroken since the war, has stalled. The eagle-eyed among you will notice that this trend established itself long before Brexit — increasing trade frictions with our nearest neighbours probably isn’t helping, but it’s almost irrelevant compared to the pre-existing growth challenge. This lack of productivity growth should shock and scare our politicians. Prosperity is in peril. It should be item number one on their agenda.

Because almost everything else follows from productivity growth. It’s not an imaginary number in the sky. It’s real people’s wages and living standards. It’s how you afford your groceries. It’s how you meet the cost of your holiday. It’s how you pay for your dad’s Christmas present. It’s taxes. It’s funding that ensures you don’t die of a heart attack waiting 12 hours for an ambulance. It’s cash for your kid’s education. It’s moolah from everything from the strength and security of your borders to the reliability and regularity of your council’s bin collections. It’s fundamental.

Stagnant productivity growth means stagnant real wages. It also means, despite the highest level of taxation since the war, stagnant tax revenue, which means stagnant or declining, underfunded public services. We’re being squeezed at both ends — by demographics, and by a lack of growth to compensate for said demographics. And the UK is vastly underperforming its peer nations.

Notably, despite having more of the very highest productivity firms than France and Germany, dominated by elite finance, law and consulting, the UK has a higher share of less productive companies. Britain does not have any substantial equivalent of the Mittelstand — productive SME firms in the regions.

The majority of Britain’s productive companies are located in London and the South East, in stark contrast to some of the poorest and least productive provinces in Western Europe in the coastal East Midlands, Cornwall and rural Wales.

So. Low productivity growth. Low wages. High individual and regional inequality. Declining public services. Strikes. National malaise. All of these outcomes are shit. We don’t want any of them.

But the oddest thing about this whole sorry mess, is that it’s a choice.

It doesn’t have to be like this

One of the reasons that the UK is currently experiencing higher inflation than its peer nations is a reduction in labour force participation – more people of working age are not working than might otherwise be expected. That means less staff, pushing up wages, worsening working conditions and raising costs. But these are cost-push wage rises, not driven by productivity gains, offering no value-add to society. The workers that receives them will see the increase eaten up by the higher cost of their morning coffee, or train to their workplace.

It had been assumed that the reduction in labour force participation was a health hangover from the Covid-19 pandemic. Who wants to work in ill-health? Could long Covid be to blame? But — why would the UK so distinctively impacted by a shared experience? The Institute for Fiscal Studies has found that while the long term sick and unemployed are getting sicker, the largest contributor to the reduction in labour force participation is older workers retiring earlier than expected.

The braindead intellectual flotsam at the Telegraph might blame ageist ‘workplace wokery’ for this increase in older workers retiring. But an actual statistics paper based on real data and a regression analysis, not vibes that sell newspapers, indicates that this phenomenon of post-Covid early retirement — which also occurred in the United States — can be entirely explained by an increase in housing wealth over the pandemic period:

For older Americans, higher house price growth is negatively and significantly associated with the probability of being in the labor force and with hours worked. Importantly, while the overall effect is negative, it is solely due to home owners.

For example, a 65 year old home owner’s unconditional participation rate of 44.8% falls to 43.9% if he experienced a 10% excess house price growth.

It seems the UK is experiencing the same phenomenon, but even more potently. Put simply, baby boomers are retiring early because they are so wealthy. And, as covered in The Triumph of Janet, a great deal of this wealth was not ‘earned’ through hard graft and prudent saving. Rather, it was accidentally accumulated by restricting the supply of new housing via the planning system.

This doesn’t just cause higher housing costs for subsequent generations, it results in economic deadweight loss across the whole of society by pushing workers away from productive employers because nearby housing costs too much to rent, let alone buy, rendering the country less productive than it otherwise could be. Locked out of the basic benefits of a liberal capitalist society like homeownership, the young are ‘breaking the oldest rule in politics’ by not becoming more conservative as they age.

The solution to our socioeconomic malaise is mind-bogglingly simple, in pure economic terms. Remove supply restrictions on housing and densify our cities and suburbs — the cost of housing will go down as supply increases, raising everyone’s standards of living. The productivity benefits of urban agglomeration will give us the income and tax take growth that will fund better and more public services.

But the politics couldn’t be more toxic and unapproachable. The British Conservative party is now the Elderly Homeowner Party. Beholden to its baby boomer voters, instead of correcting for its socioeconomic failures by pulling the steering wheel back to the middle, it is steering into its problems.

The problem is, the resultant accumulated failure is finally starting to have an impact on its voter base. For over a decade, the burden of austerity and low growth has been shouldered by the young. Now, baby boomers and the Conservative Party are finally coming to enjoy the bitter fruits of their political labour.

Any movement to end the immense power of baby boomer homeowners to block housing development near them is immediately met with a wall of resistance, both externally, from voters, and internally, from craven and intellectually weak MPs. There is nowhere for the party to turn. The young hate the Tories; all that’s left to do is increase the turnout among the old core vote.

The Terry Pratchet novel Jingo describes the problem of leading a donkey back down the narrow staircase of a minaret. First tempted to start climbing, then locked in by path dependency, the only way is up, regardless of what awaits at the top. But I tell you this. The view from the summit will be worth it.

'Er–' said Colon. 'We have plenty of donkeys,' said Lord Vetinari. There was general laughter, most of it directed at Colon. One of the men pointed to the dim interior of the minaret. 'Look. .. see?'

'A very narrow, winding staircase,' said the Patrician. 'So... ?'

'There's nowhere to turn at the top, right? Oh, any fool can get a donkey up a minaret. But have you ever tried getting an animal to go backwards down a narrow staircase in the dark? Can't be done.'

'There's something about a rising staircase,' said someone else. 'It attracts donkeys. They think there's something at the top.'

'We had to push the last one off, didn't we?' said one of the guards. 'Right. It splashed,' said his comrade in arms.

It’s not that senior Tories haven’t started to notice these problems (13 years into government). But the solutions offered are completely unserious and do not challenge the fundamentals of why we are here. Enterprise, education, employment, everywhere. Noble, well-intentioned window dressing.

It’s not a political economy distinct to conservatism. On the other side of the Atlantic, the Conservative Party of Canada’s own Leader of the Opposition, Pierre Poilievre, is actively and loudly attacking the incumbent Liberal government’s record on the cost of housing.

Elsewhere, the centre-right New Zealand National Party recently endorsed a cross-party reform to enable densification aimed at solving the Kiwi housing crisis, following on from earlier zoning reform success. Success that is enabling housebuilding and starting to bring down prices in one of the most expensive real estate markets in the world.

It seems it is just the British Conservative Party that doesn’t have the moral courage to stand up for what is right. To stand up for a political economy that can offer us good, well-funded public services. To stand up for a political and economic philosophy that could deliver better living standards across the generations.

The only thing left to do push the Tory donkey off the political minaret at the next election. Let’s see if it floats.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost I owe huge thanks to John Burn-Murdoch and his exceptional colleagues at the Financial Times for their fantastic, data driven reporting that this analysis has so relied upon. John is one of our country’s finest data journalists and is always worth reading.

I am also privileged to know a number of doctors socially, all of whom have added to my understanding and thoughts on the the British healthcare system over time. Thank you to each of them.

If you enjoyed this post, check out the Triumph of Janet, which covers similar themes!

"But put aside any emotions — the market does not give a flying fuck what you think about social justice — it just is. If the market price isn’t good enough, the marginal supply of labour will reduce, and you need to be prepared to put up with the consequences of that for your righteous vibes."

This this this. Amazing to see so many supposedly 'pro-free market' newspapers conveniently fail to see that the labour market also applies to the public sector. I do wonder if they've run so many pieces about how public sector workers 'couldn't get a job in the real world' that they've started to believe it.

It's worth noting that the Liberal Democrats, despite being nearly forgotten in the national narrative, have played a huge role in this. Not through their participation in the 2010-15 coalition, where in fact I think they were a largely positive force (though not as strongly as I thought at the time - I was a member from 2010-2019), but through their utter capitulation to the "localist" wing of their own party since their 2015 electoral drubbing.

The party has almost no power left, but uses most of what it has to pound the Conservative party *from the NIMBY direction*, making it clear through the Chesham & Amersham clown show that if the Tories back off their dedication to maximising homeowner wealth even slightly, they'll get electorally hammered. You'd have hoped that a party with as comfortable a majority as the Tories currently enjoy, and certainly with the kind of decent polling position they did have back around the C&A by-election (which was before the recent chaos at the top) would have the breathing space to not have to constantly red-line their appeal to their extreme wing. But this can't happen, because the Liberal Democrats have slipped into the role that used to be played, at least in theory, by UKIP, of keeping the Tories anchored to their base by threatening their core vote if they took a more pragmatic course. But unlike UKIP, the Lib Dems have actually followed through on the threat and shown they can actually dole out the punishment, whereas UKIP was only ever talk.

This is an extremely painful reality for me, as I was a pretty partisan Lib Dem for a long time, but the NIMBY wing that was always poking around doing damage got a huge boost in 2015 and then inexorably tightened its grip over the following years, eventually reaching a point where I couldn't continue.