Cutting immigration won’t solve housing 🏘️📉

Beware the siren call of simplistic solutions to multifaceted problems

If there is a ‘dog that didn’t bark’ in the recent Tory leadership election, it is the subject of immigration. Distracted by a grim butcher’s slab of more immediately pressing issues facing the nation, including rocketing inflation and interest rates, a looming recession, and the war in Ukraine, the subject barely surfaced over the entire leadership news cycle.

That’s quite the fall from prominence for a subject that ranked above all others in 2015, at a heady 86%, as the most important issue facing the country for people intending to vote Conservative. Today, the number saying the same has more than halved. When the topic has managed to surface in the news at all, the focus has been on one area alone: illegal immigration. Arguing over net migration figures was, it seems, a means to an end — for securing a vote on – and winning the EU membership referendum alone.

Today, in stark contrast to the total obsession on net migration a few years ago, the contest saw only passing mention on the subject, usually relating to the small boats phenomenon, such as Rishi Sunak’s quietly released ten point plan on illegal migration, and affirmations of support for the existing Rwanda policy on refugees from both candidates. This was despite net migration standing at essentially the same level as before the referendum result, even after leaving the EU.

A rare exception to this during the contest was Conservative MP Neil O’Brien, who made the case for reducing net migration to reduce the pressure on Britain’s dysfunctional, overpriced housing market.

‘To reduce demand we must reduce immigration. Otherwise, [...] we’re running up the down escalator. Over the last decade, migration directly added two million to the population, equivalent to the populations of Nottingham, Derby, Leicester, Middlesborough, Carlisle, Oxford, Exeter, Portsmouth and Southampton combined,’ O’Brien said in an article on Conservative Home, one of the most influential sources of party news and opinion among Tory MPs, councillors and members.

It would be remiss of affordable housing campaigners, whose message is dominated by messaging on supply side reform, to ignore this call. Reform planning – actually allow this country to build houses – and the problem will solve itself, by finally allowing supply to meet demand, their argument goes. But what about demand, which is, after all, the counterparty of supply?

Indeed, anyone who has glanced at the comment section below an article on housing affordability, regardless of the publication and the political leanings of its readers, will see comment after comment stating that the opposite approach — cutting demand — is the obvious solution to high prices, adding that nobody is willing to talk about it.

‘These daft liberal young snowflakes don’t need new houses in my back yard, they just need to cut immigration,’ one may satirise their position. And to be fair to them, these comments align with my own personal experience. I wasn’t the only potential buyer looking at a property in the past few weeks. Among the prospective buyers were internationals, ready to compete on price.

There’s just one problem with cutting migration to solve house prices, however. It wouldn’t work.

An acute housing shortage in this country already exists right now. Short of the ethical sewer that is migrant repatriation, the best cutting immigration today could do is not make things better, but to prevent the existing chronic supply shortage getting even worse tomorrow. This seemed to be O’Brien’s point, who continued by referencing research by Migration Watch, which found that migration at current levels ‘will generate the need to build one home every six minutes, night and day.’ But this comes with adverse consequences.

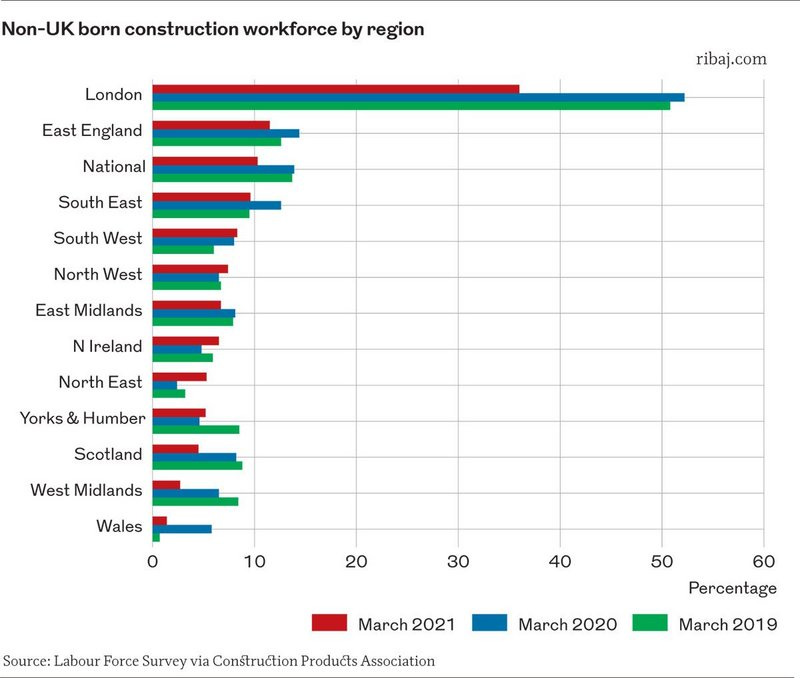

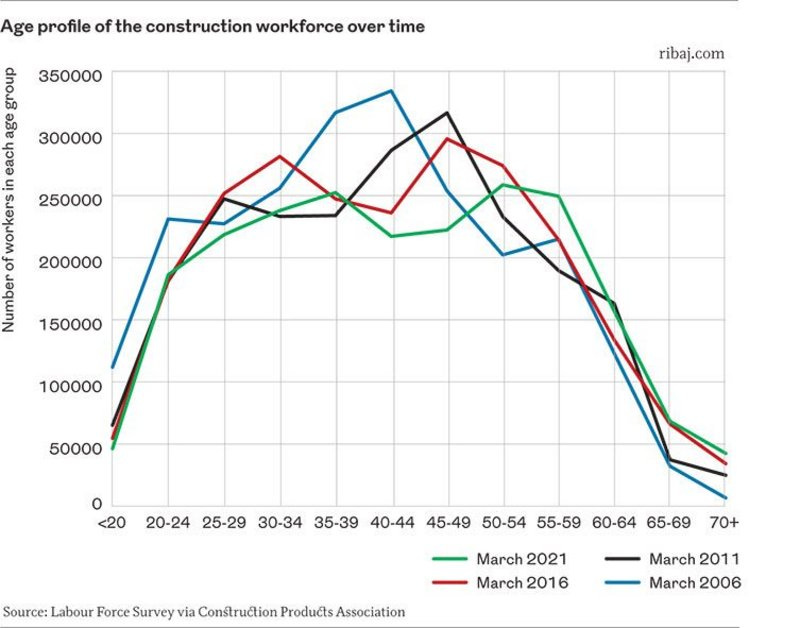

Over half of workers in the construction industry are not white British. Turn off the migration tap, and we’ll have even fewer construction workers able to build the housing Britain desperately needs. This effect would be felt most bruisingly in Britain’s cities, which host a higher proportion of migrant workers in construction, and, as prices tell us, are the areas most in need of new housing construction. We need these workers. Even before this, post-Brexit, the industry is facing a worker supply crisis, which is already delaying projects. And a large cohort of 50-60 year olds in construction is also approaching retirement. The last thing the sector needs is another throttle on the supply of workers.

Population growth, meanwhile, is not just driven by migration. It’s driven by births, too. Nationally high fertility in the postwar period drove the surge in births that gave its name to the ‘baby boomer’ generation. Under a population growth rate that, at its peak, was actually higher than the last few decades’ population growth rate, we didn’t see housing affordability stretched to breaking point. The reason is simple: then, we actually built houses. Harold Macmillan’s Conservative party was not defined by NIMBYism and its myriad consequences, instead it was a patriotic, house-building, nation-building party. Cutting the population growth rate is not necessary to make housing cheaper.

In fact, because the boomer cohort is so large, and was followed by a dearth of births, there’s another problem: the dependency ratio. This is simply the ratio of working age people to non-working age people – those of school and pensionable age. After declining steadily for about 40 years – from 1970 to 2010, the dependency ratio is rising. And it’s rising rapidly. That means there will be relatively fewer productive workers to pay income taxes to fund the state pension and public services – public services that will need to expand in scope and scale to deliver health and social care for a large cohort of elderly baby boomers, with more complex and expensive health and treatment needs.

With fewer workers, the costs of providing this care will rise as worker supply shortages bite, raising wages in the health and social care sectors which, much like construction, are already in crisis from a lack of worker supply. The rising per-individual cost will be multiplied out across the large, retiring boomer cohort. And, based on previous behaviour, I wouldn’t bet the house (that I don’t own) on the baby boomer generation voting to tax its own huge, unearned asset wealth to pay for its own health and social care instead.

That cost can be passed down to the children and grandchildren. They can pick up the bar tab. Again. From the high costs of supply-restricted housing, to the future impacts of climate change, to servicing national debt, to protecting the elderly with lockdowns that do not personally benefit them: the young exist today to be servants and debtors to the elderly.

The blunt truth is that focusing on migration is yet another diversion from the actual solution – building houses to meet demand. Like campaigners that say ‘brownfield first’, it’s just a distraction – a mere talking point. A catch-all, get out of jail free card that enables politics and politicians to avoid confronting vested interests and committing to action that would make a genuine difference.

Being opposed to immigration is often framed through the lens of patriotism. ‘I want to defend and protect my country for its own.’ Cutting migration tomorrow under the guise of helping the young afford housing would do the precise opposite. To truly be a patriot, you must want a sustainable, better future for your country and its young. To truly be a patriot, you must make peace with immigration, and build some bloody houses.