Let's defeat Ronnie Pickering, once and for all 🚘🤬

The choices we make are a product of our environment – we can change them for the better though stakeholder-engaged design

Conflict

Conflict is a seemingly inescapable part of life. That is not to say that all conflict, ‘a serious incompatibility between two or more opinions, principles, or interests,’ is inherently bad. While we may immediately think to the negative connotations of the word, conflict can have highly beneficial outcomes to its participants. Identifying opposing interests, and working together towards a mutually agreeable or acceptable outcome, begins with conflict.

Indeed, for couples, certain forms of conflict are even associated with relationship satisfaction and longevity. ‘Recent research has challenged assumptions that disagreement and opposition is bad for relationships, and softening conflict with affection, forgiveness and validation is good,’ one literature review concluded.

Meanwhile, political systems that design out meaningful ideological and practical conflict – for example, by suppressing dissent or freedom of press – converge towards dictatorship and sclerotic social, economic and environmental outcomes, demonstrated most vividly by the former Soviet Union, and indeed modern Russia.

Conflict may also be further categorised along a sliding scale of necessity. ‘The question for us now is to be or not to be,’ Zelensky told the House of Commons earlier this year. Russia’s invasion has forced Ukraine into an existential conflict – the very essence of necessity.

Less existential, but still highly necessary for good social outcomes, is the conflict between competing businesses in a marketplace. One example is the competitive conflict we see between supermarkets, which is associated with lower consumer prices. A store may wish for lower local competition to increase its profit margin, regardless of whether this is to the benefit of wider society –competitive conflict introduces incentives that act against excessive margin.

The necessity of some conflict may also be situational. While some workplace conflict is necessary, characterised by stakeholder engagement, negotiation and implementation of mutually agreed developments in strategy or operations, many workplace conflicts are driven by a lack of communication and empathy.

Some conflicts are not caused by some grand ideological showdown, innate mutual distrust or naturally competing interests. Some conflicts, many of which have no socioeconomic value, are a passive product of system characteristics – such as the conflict escalation mechanisms inherent to asynchronous, text based communication channels like instant messages or emails – and poor system design. And we should seek to identify and mitigate, account for or eliminate these harmful, unnecessary conflicts from our lives.

Independence

You are a rational, intelligent adult, with the ability to make independent decisions for yourself, on your own terms, with nobody telling you what to do, right? Wrong. Plenty of decisions that you make – including some with harmful outcomes to society – are passive outcomes of system design.

A every-day example of this is something as mundane as road junction radii. Road junction radii can be calculated by drawing a circle tangent with the continuous road surface in both junction directions.

‘Relatively minor adjustments to junction geometry can have a significant effect on the speed of turning vehicles,’ TfL advises in its London Cycling Design Standards document. Indeed, this has been quantified by highway engineers:

Manual for Streets sets out some of the passive choices made by both drivers and pedestrians when using junctions with large radii, which include:

Higher, more dangerous turning speeds

Greater pedestrian timidity in establishing priority

Longer walking routes for pedestrians seeking to find safer passage (of particular concern for the less able)

Requirement to scan a greater field of vision to establish crossing safety

These are all passive outcomes of junction design that can instigate conflict between pedestrians and drivers. Pedestrians are likely to find higher turning speeds aggressive and threatening. The driver may not even be aware of this perception, while the benefit of a wider junction to them is entirely marginal and of little utility – fractions of seconds gained back while turning, and perhaps less brake wear and fuel burn. All this conflict for a passive, unnecessary choice, driven not by intention, but unthinking infrastructure design.

Some of our most attractive, modern infrastructure designs are not sufficient to prevent modal entitlement. Were this driver to follow the highway code and prioritise the most vulnerable road users, they would give way.

Even the form any conflict takes itself is not necessarily within our control. Flooded with adrenaline after a deadly near miss, a cyclist or pedestrian is far more likely to act with anger or aggression than a driver behind 2 tonnes of airbagged, crumple-zoned steel. This in turn is more likely to make the driver think and act less empathetically to the next individual.

It would be unfair to suggest that the highway engineering profession is unaware of the consequences of not analysing and accounting for the impacts of design, as the breadth and depth of academic research and proliferation of design code documentation demonstrates. But given that wide radius junctions still exist, are even still being built, and the conflict caused by them is a) not socially necessary and b) not socioeconomically beneficial, we should seek to eliminate them from the public realm wherever possible.

In fact, all conflict between transport modalities has no socioeconomic benefit. At best it results in an inconvenienced or scared vulnerable road user, while at worst, it results in life-changing injuries and and deaths. Is intramodal conflict even necessary?

A grim example of intramodal conflict. The driver doesn’t even get out to confirm the child is ok.

If junctions with wide radii were utilised by only motor vehicles, the only substantial conflict would be over cost and land use efficiency (i.e. the land used for this wider junction could be used for another purpose with higher socioeconomically value .) The reason junction radii matter in mixed settings is the convergence of transport modalities, which have different innate:

Speeds

Vehicle weights (& collision energies)

Perceptions of safety

Physical safety features (e.g. crumple zones, airbags, mirrors)

Braking distances

Agilities

Abilities to handle rough or badly maintained road surfaces

Perceptions of entitlement to road space

This gap in experience of the same space leads to conflict through variance in expectations of what is reasonable. A driver is likely to find higher speeds on a rough road more reasonable than a cyclist, potentially triggering impatient or defensive behaviours that encourage conflict. A sense of intrusion on the individual’s expectation for how public space is used doesn’t even have to be between large, heavy motor vehicles and pedestrians, it can be mild speed differences on a relatively thin canal path.

It doesn’t matter that the aggressor in the video is spouting unreasonable and spurious nonsense, the point remains that his perception of reasonable public space utilisation based upon his (dominant) modality, has been intruded upon.

Accommodation

The canal in the video is likely to be the most direct, safe and pleasant way for the cyclist to get to his destination. In most cases, the alternatives will be dangerous, loud and unpleasant roads, dominated by a single modality (motor vehicles). When polled, two thirds agreed that ‘it is too dangerous for me to cycle on the roads’, a figure that rises to 71% for women.

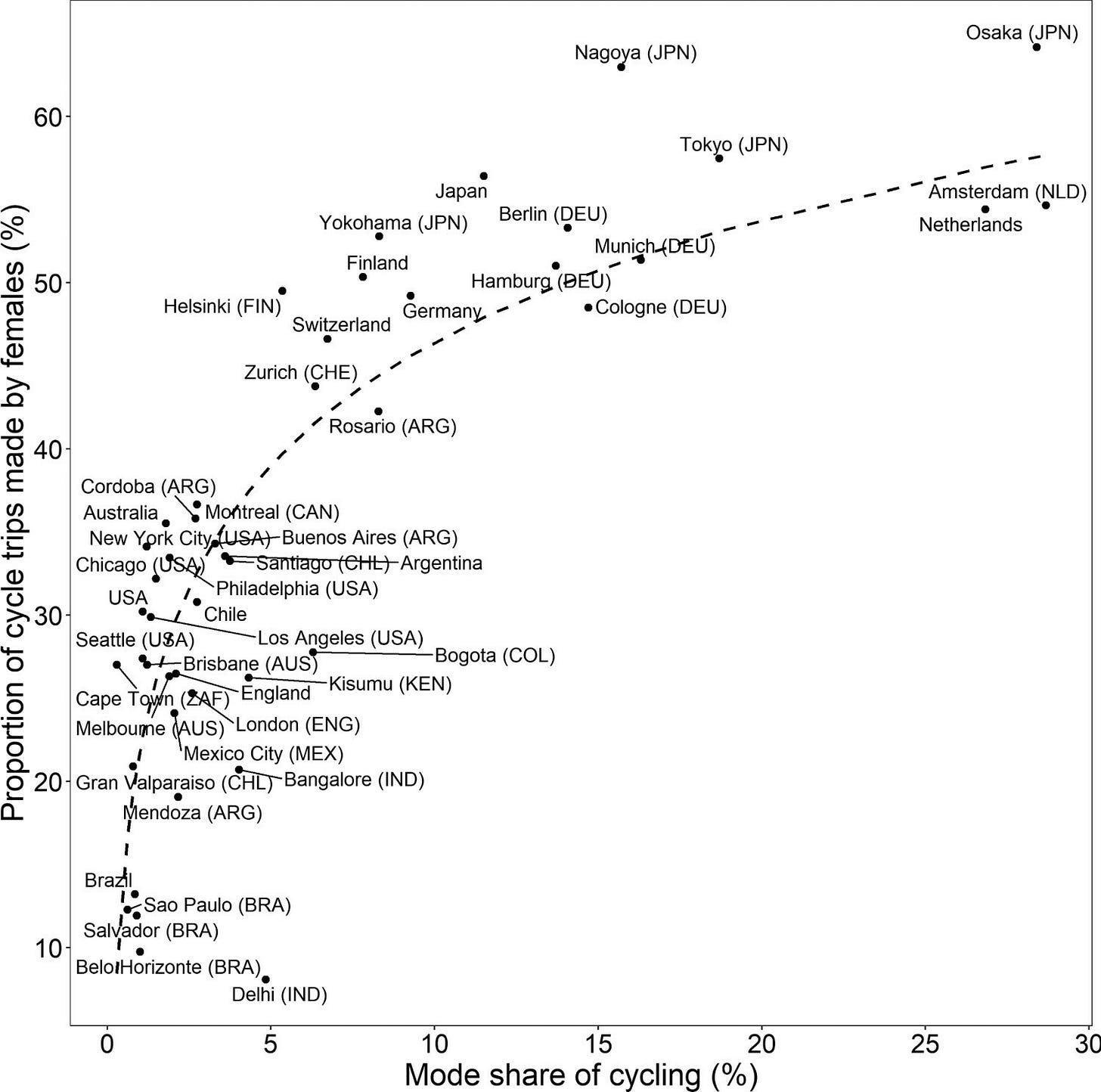

In fact, conflicts are likely have differential outcomes based on sex, race, mobility and other immutable characteristics. A simple proxy measure for the inclusivity, safety and health of a space or institution is the proportion of women that participate in it.

Respondents to polls on cycling safety are correctly identifying the likelihood of conflict happening during routine journeys. The answer is to design out conflict in the first place. No party is satisfied with conflict-inducing bimodal infrastructure, be that car-bike or e-scooter-pedestrian. And like with our junction radii example earlier, it is possible to design systems in a way that reduces or eliminates conflict.

Even the best multimodal transport infrastructure cannot account for entitlement like this.

For transport, this means segregating modalities, deprioritising and slowing more dangerous modalities, and being active, not passive in understanding how systems shape our choices and outcomes.

But this it too expensive, is politically impossible, will increase journey times and take the roads from what they were designed for – motor vehicles. Right? TfL estimates that implementing segregated cycle infrastructure costs £1.15-1.45 million per kilometre. This is a drop in the ocean compared to overall transport infrastructure spend – the redevelopment of a single Bedfordshire roundabout has been costed at £1.4 billion. Cycle infrastructure even pays for itself, with a competitive return on investment versus other government spending.

Safer infrastructure facilitating higher physical activity is also associated with better, cheaper healthcare outcomes, increased spending in local businesses, less noise, air and visual pollution and more cohesive, open communities.

And despite the perception of many that segregated cycle infrastructure slows down vehicular traffic, this is not borne out by research. Even if it were to, what are the roads for - people or motor vehicles? This definition has changed over time – for the worse. The right of an individual to travel from A to B safely should not rely on their modality – a strong proxy for wealth, income, sex and race.

It’s easy to assume that these schemes impossible to implement because of local opposition. But while you may see a vocal minority voice their disapproval, measures for walking and cycling have overwhelming support from the population.

So if there’s no benefit to this conflict, and it doesn’t even need to exist, and fixing it actually yields better social outcomes, why hasn’t it been fixed? Inertia. Urban planners are finally noticing this and accounting for it now, after decades of campaigning and research, requiring communication and empathy with all modal stakeholders.

And so this is the lesson from this post: Notice the conflict in your life caused by poor, unaccountable system design that does not engage all its stakeholders. This could be at home, at work, or in life generally. Next, work out causes and the incentive structures that define that conflict. And eliminate that conflict through better, inclusionary system design. You’ll live a happier, calmer, more productive life for it.

We've been socialized into subservience by the two-tonne hydrocarbon missiles that are clearly the dominant lifeform in our cities. Twice daily I participate in an incredibly complex and agonizing group effort so that some chunk of shiny metal can creep through Marylebone at 9km/hr. On the street, I am encouraged to ignore the stream of unfathomable kinetic energy and momentum, the vector of which could be rotated 3 degrees and turn someone into a mass murderer.

Dropping the bit - the anger I have for cars and drivers is clearly a result of what you describe, a form of (probably unnecessary) intermodal conflict in a big transport game. It benefits me as a rational agent to push back against drivers such that I can alter the current equilibrium to my benefit.

Yet I have no strong allegiance to any mode of transport, so why does any conflict arise at all? As in - if think cars are so much better why don't I just switch? Herein lies the real problem, I suspect, the transport game is really a proxy for something like inequality.

On another note completely - my first job was for an ANPR company, during my time there I inproved the accuracy of their main OCR model by a few percentage points. I would like to think this has resulted in fractionally safer roads and a few million extra in fines.

Thanks for the thought provoking read!

Putting cycle lanes on Euston Road is sheer madness.