Reform UK is where angry Conservatives go

What defectors present as conviction is often restless agitation — a despairing, resentful lack of faith in a country they invoke much more than they inhabit

The bubbling brook of former Conservatives that have defected to Reform UK widened into a small stream yesterday, with former Home Secretary Suella Braverman announcing she had quit the Tories and joined Nigel Farage’s insurgent party. ‘We can either continue down this route of managed decline to weakness and surrender. Or we can fix our country, reclaim our power, rediscover our strength,’ she told an assembled crowd of supporters.

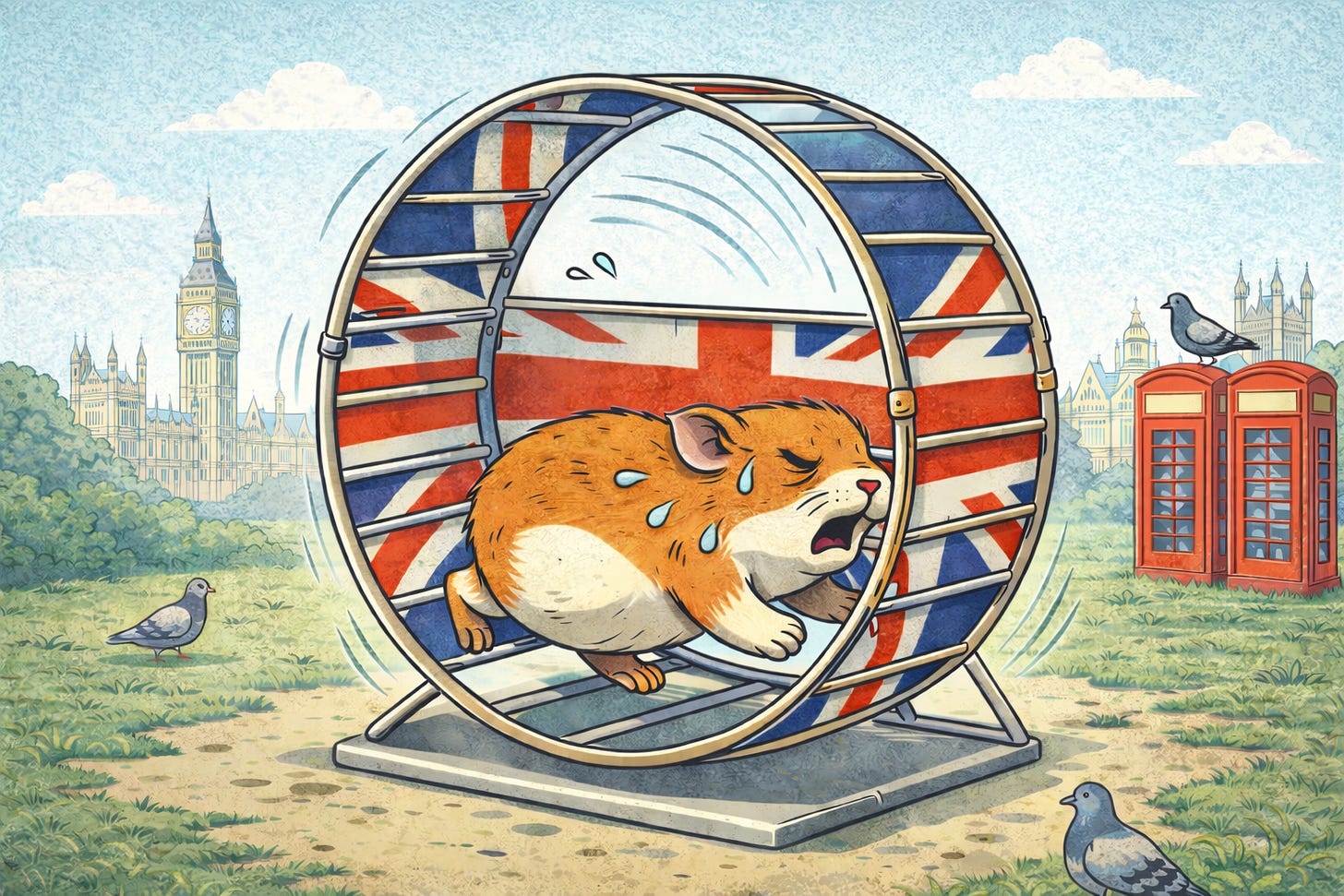

This is a narrative Reform will be keen to project following its third sitting MP defection in less than two weeks: that a trickle of departures is becoming a thunderous torrent of Tory talent, scouring out what remains of the Conservatives and destined to put wind back into Britain’s slack sails of stagnation. Braverman’s defection speech was lofty, ambitious and radical — and quite angry. Britain is ‘broken’, and ‘weak and humiliated’ on the world stage, she said, echoing Robert Jenrick’s own departure, in which he branded the government’s energy policy ‘suicidal’.

‘They run Britain like they hate it,’ Jenrick added last week. This is not the language of custodianship or repair, but of rupture and emergency. It is not the prose of plodding and deliberative Tories – this is the heated rhetoric of impatient and agitated radicals, ready to charge at every fence they find in their way, blocking the path to victory. If there is one, the purpose of the fence can be discovered later.

Braverman opened her defection speech by saying: ‘I feel like I’ve come home.’ Whether she intended it or not, her quip hit the nail on the head. The former Tories joining reform have every right and reason to be impatient about getting Britain back on track – its problems are manifest and deep – but it’s historically unusual for British conservatives to be quite so revolutionary and reactionary in the words they use to describe their politics.

While Reform’s upper ranks are increasingly being dominated by impatient Tory cast-offs, an opportunity is emerging for Kemi Badenoch’s Conservative Party to retake some of its historically important ideological territory. That Burkean tradition of preservation, caution in change, and respect – but not reverence – for institutions.

The ideological underpinnings of decades, if not centuries of Toryism were discarded in the last decade, to the radical chaos of the EU referendum and its aftermath. These conservative values sometimes seem more an innate human disposition than a deliberative, ideological and rationalised positioning. It’s the humble English antidote to the belligerent and activist conservatism of the United States.

If Badenoch chooses to pick up and run with this lost strand of Tory thought, she will need to walk a tightrope. She would need to find a means of communicating an honest and uncompromising assessment of the failures of liberal institutions to deliver in recent decades, and the need to enact thorough reforms – all while not just defending, but fighting for their very right to exist. ‘What will fill the space of what has been destroyed?’ is the question not being asked.

Former West Midlands Mayor Sir Andy Street and Ruth Davidson, former Scottish Tory leader, spoke out for exactly this vision on Sunday. ‘There is still a really, really strong centre-right who believe in Britain, believe in its institutions, believe in its future, and who want to build things up, and not knock things down,’ said Street.

‘This is about people that feel that the Conservative party left them but also feel like they don’t have a home in Labour or the Liberal Democrats,’ Davidson added. It’s a quaint, hopeful vision that feels oddly nostalgic, and naive in equal measure. It’s like unearthing a time capsule buried at the London 2012 Olympics.

Politics has changed at a rapid, frightening pace since then – nationally and internationally. Much that has been taken for granted for decades has now come into play. It is for liberal institutionalists, not revolutionary radicals, to come up with the reforms that empower and, even more importantly, moat the liberal structures that they value. For voters, raw outcomes will always, quite literally, ‘Trump’ process, procedure and philosophy.

Without delivery on migration policy and its implementation, and stagnating living standards, liberal institutions have a limited shelf life – no matter their historic, moral or theoretical value. And that’s before factoring in how short form video feeds are influencing our perceptions of our own lived reality. The emotive and algorithmic politics of agitation, resentment and anger that keeps you tied to your black mirror is a potent social media business opportunity.

A glowing red top that lives in your pocket, goes to the bathroom with you, rests beside you at night, and offers an infinite open window facing out onto all that makes you despair. And everyone has one, from your dentist to your grandmother. Does deterministic, 20th century liberalism have any answers for these existential challenges? If it does, we are yet to find its communicators.

The politics that Davidson and Street speak of is rich in intellectual tradition – and has supported many historic Conservative election victories. But let’s say they get past the first hurdle of finding a way to both criticise and cherish the structures of state, and come up with a viable means to reform them such that they actually deliver again. Does a viable Tory electoral coalition for this vision even exist in this new, post-postwar politics of funhouse mirrors?

Great than we just need to see how anger eats itsself, as it uses to