The Great British Housing Famine

Yes, it really is as simple as building more homes

Bush legs

What is the first country that comes to mind when images are invoked of a line of weary citizens, queueing up to purchase basic goods in limited supply?

It’s likely you thought of the USSR, where so-called bread lines became a hallmark of the late Soviet era. These queues left us with enduring images depicting the failure of a modern, developed state — with the second most successful space agency in the world — to reliably deliver groceries to its people.

By the late eighties, the destructive influence of centralised five year economic plans, market interference and price controls had over-spilled into the general availability of food, books and clothing. Just about everything required lining up and waiting, often for hours, with no guarantee that what you desired would still be available when you reached the front of the queue.

If you cannot determine access to goods by price, demand can only be allocated by first-come-first-serve and subsequent shortages, or rationing — or some combination of both. Even in a system of allocative rationing there will be systemic leakage, as unavoidable market pressures forcibly reestablish themselves through informal arrangements and favours, black markets, and of course, outright bribery.

Likewise supply. Because prices could not be set by a combination of consumer preference and the cost factors of production, Soviet farmers were forced to supply whatever meagre, underwhelming produce that fixed prices could allow them to produce.

This led to the phenomenon of ‘Bush legs’, where ordinary Russians were shocked by the size, taste and succulence of more than 200 tonnes of free market chicken imported to Russia from the United States, following a 1990 trade agreement signed by then Soviet leader, Michael Gorbachev and US President, George H. W. Bush.

Supplier? I hardly know ‘er!

Another country you might have thought of when asked to picture a line of weary citizens, queueing up to purchase basic goods of which there are limited could be the United Kingdom, where there is a severe shortage of supply relative to demand in housing — where people will literally queue in their dozens to view a small two bedroom terrace house. To rent, not to buy, of course.

Queues don’t have to be physical lines of people, as anyone trying to contact a utilities provider by phone will be well aware. The BBC reported last year that the average queue of tenants requesting to view a retail property has lengthened to 25 — up from six in 2019 — with prices increasing by 10% between July-September 2022 and 2023, using data from Rightmove.

Ria Laitmer, lettings manager at Clarkes agents in Bournemouth, said: ‘The gap between high demand and a severe shortage of rental stock at the moment is just crazy.

‘We're receiving mounting enquiries for each property to rent from would-be tenants, with queues of tenants arriving to open-house viewings and the majority being left disappointed as there are just not enough properties on the market to meet the demand.’

So far, so familiar. But unlike in the Soviet Union, we are lucky enough to be able to much more freely observe price signals, distorted as they are, in addition to noticing queues. Prices are a very important piece of information. They tell us the equilibrium point of demand relative to supply. The point at which free agents are willing to exchange goods and services.

Japanese holdouts

We are being told in the clearest possible terms, by the highest house prices since Queen Victoria was on the throne, that housing supply is not adequately able to respond to housing demand. Most goods become better or cheaper relative to incomes over time (otherwise, what would be the point in economic growth?) British housing, along with many other countries with restrictive planning policies, is an exception.

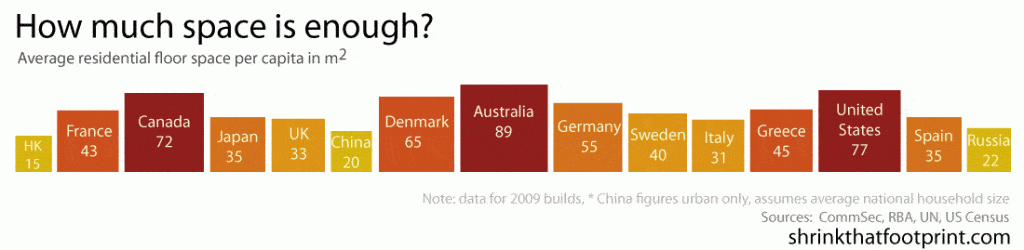

We might also look abroad and see our own equivalent of ‘Bush legs’ when we compare the quality, abundance and floorspace of housing in other, comparable developed nations. If you are a prolific scroller of TikTok, you might have noticed that videos filmed in an average American home have rooms that look much nicer and are substantially larger than TikToks filmed closer to home.

Scarcity also leads to all possible personal efficiencies being made in the consumption of goods. The UK has one of the lowest proportions of vacant dwellings in the OECD, precisely because housing is so expensive — caused by the relative shortage of homes per capita. People must make the best of what they are being allocated by the rationing system.

The UK also has shrinking floorspace per person in the faster-to-respond and expanding private rented sector, as houses are subdivided into flats, living rooms are converted to bedrooms, and cost-squeezed tenants move into smaller properties to manage their personal finances and account for the systemic supply shortage. Younger renters would like to consume housing equivalent to or better than generations before them, but this is rendered unaffordable by rationed housing supply.

It’s rather odd, given the abundance of evidence that we have a supply crisis, that we still see supply deniers or doubters in the housing policy space — appearing like Japanese holdouts hiding in ideological jungles, long after the end of the war.

The spectrum runs from nakedly anti-growth and living standards supply denial, to softer scepticism that revolves around the idea that supply and planning reform is necessary and good, but not sufficient, to make housing more affordable. A report released by the Social Market Foundation (SMF) this week sits at this well-meaning end of the spectrum.

The report accurately describes much of the governmental and policy landscape on how our planning system restricts the supply of homes. It also fairly covers the advantages, disadvantages and potential political difficulties and disappointments that planning reforms, with the aim of increasing build-out rates, might run into. But if we follow some of the logic in the report to its conclusion we must infer that we have created a perpetual wealth machine, which would be a surprising finding.

Even where supply does increase, there is no guarantee the increase will be large or that the new units will be affordable. In fact, planning reform has in some cases been blamed for worsening the affordability crisis through gentrification, as changes to the land’s capacity increases its land value without increasing supply. Here we refer to ‘gentrification’ as the disproportionate increase in local home prices or rents relative to the region as a whole.

In cases like New York, new units worsened affordability by building at or above market rates or being designed as “luxury homes.” In these cases, policymakers promised that the deflationary effects caused by the new supply would outweigh the inflationary effects of higher prices. Yet in practice, limited supply and high prices combined to decrease affordability.

If prices do not fall when additional supply is delivered, then we have either found a way to generate infinite wealth by building as many homes as we can — or, as seems more likely, we should draw the opposite conclusion from building homes is not the long-run answer to affordability.

Instead, we should understand that housing demand is extremely inelastic, precisely because the shortage is so severe. In other words, people are so desperate to consume more housing that they will pay extortionate amounts to receive even the most desultory crumb.

The SMF report appears to assume that upward trends in planning permits is an ongoing inevitability, rather than something that may require sustained political and policy pressure to remain feasible, and focuses in on narrow time windows.

It does, however, correctly identify that planning reform that appears to improve permitting on a surface level will not result in more planning consents or houses unless it can reliably deliver government approval outcome as well as intent, and is unconstrained by the details of adjacent policy areas.

This is an argument for a better policy development and implementation, not an argument against supply-side reform as an answer to the affordability question.

More broadly, a common theme on the left end of the housing policy spectrum is (likely unintentional) data dredging to facilitate supply scepticism and avoid market-based solutions. Novel research that goes against the consensus is more likely to be noted and shared, especially if it facilitates an easy answer for politicians keen to avoid telling existing homeowners that building in their back yard will, in fact, be necessary.

Another left focus is affordability requirement policy solutions. Such requirements necessarily make development more costly or less beneficial for developers (or these would not be mandated by policy) and are one of the ways most western governments have attempted to make housing more affordable for the last 20 years: trying to use regulation to regulate existing regulatory outcomes into into behaving properly. Price signals be damned.

This approach to housing can be expressed in various ways: affordability requirements for developments, rent controls, and the UK Government’s Help to Buy government loan scheme, Help to Buy ISAs, and Lifetime ISAs. Each are a demand-side attempt to argue a market into submission. But markets fight back.

The Great British Housing Famine

The SMF report suggests the following:

Affordability requirements following a 60-30-20 rule which provides tax incentives for property if they agree to a price such that households making 60% of the local area’s median income do not need to pay more than 30% of their wages on rent or mortgage payments in 20% of units.

A focus on affordability over supply puts the cart before the horse. If we look to other examples of extreme supply constriction, such as famines, would not advise against delivering additional grain to the affected region unless it is ‘affordable’.

Delivering one additional sack of wheat will not lower the market price. But that does not mean that it will not be hungrily consumed, or that it cannot represent the beginning of the end of a supply crisis, should it be the first of many more. If prices do not fall when supply is delivered, this indicates consumers are very hungry for the good or service they are purchasing.

Subsidising housing rents or purchase prices, or mandating ‘affordability’ (when supply is constrained) forces wider market rents and prices to rise. There is no supply escape valve that can respond to the additional capital input or restrictions, which means market prices are forced to rise with no additional quality or quantity benefit to housing consumers — unless the consumer already own housing equity, which will increase in value.

Even then, this only advantages them relative to their peers without capital. What use is an expensive, low floorspace, poor quality house compared to a cheap, high quality, high floorspace house?

Demand side subsidies with restricted supply therefore represent a large additional transfer of wealth to the existing owners of capital, topped off with access to even greater economic rents — with profound implications for wealth inequality, intergenerational inequality, and the social contract itself.

We might say this is worthwhile, if it means that housing becomes ‘affordable’ through subsidy to the least well off. But it is a cursed choice of temporary convenience, and delivers affordable housing by lottery. It forces cities to play host to inefficient labour markets, encouraging high-productivity workers to give up and seek better living standards elsewhere, while not addressing the core reason for the affordability crisis, and doubling down on the deadweight losses of restricted housing supply.

Folk economics

Focusing on policy-mandated affordability over supply seems to be an expression of ‘folk economics’ — how people intuitively understand economics. For housing, folk economics diverges substantially from the observable and measurable reality in a way that it does not for other markets.

Nall, Elmendorf, and Oklobdzija, found that: ‘30%-40% of Americans believe, contrary to basic economic theory and robust empirical evidence, that a large, exogenous increase in their region’s housing stock would cause rents and home prices to rise.’

Perhaps this is simply an expression of how illiquid real estate is. It is far easier to imagine a supply shock causing a price rise or fall in oil, and subsequently in petrol prices. Maybe the infrequency of house purchases and the emotional connection to our own homes is the cause of the distortion.

But when it comes to solutions, we can continue celebrating affordability criteria like tractor production figures, or can start to notice the large queues outside the bakery. There is a housing famine.

We have tried demand subsidies, as have many of our peer nations, time and time again — in guises as varied as Help to Buy, affordability criteria, shared ownership and targeted ISAs. Yet we still have one of the worst housing affordability crises in the world. What conclusion should we draw from this?

A great read.