Labour must grasp that growth is a choice

It's not enough to believe in ends – Labour must believe in a means to growth

A growth journey

Growth is the defining mission of this government. It is the only way to deliver our Plan for Change and put more money in people’s pockets. The only cure for the sickness of stagnation and decline. – Sir Keir Starmer

I don’t think we talk enough about how interesting and profound Labour’s journey on economic growth has been. Barely five years ago, economic growth was an abstract concept owned by the ‘80s tribute band on the other side of the Commons. It was Tory territory, defined in Thatcherite terms: free enterprise, privatisation, deregulation. Pinstripe suits, Canary Wharf and impractically enormous mobile phones that made you look like a cross between a pillock and a twat.

If Labour considered economic growth at all, it tended to be through the lens of ‘industrial strategy.’ Which usually meant subsidising sclerotic and uncompetitive industries producing things that nobody wanted, in order to prevent decline and social crisis in constituencies dominated by primary and heavy industries – until crisis meant it happened anyway, and quickly and in lockstep instead of gradually and independently. Now, economic growth is the declared ‘defining mission’ of this Labour government.

The usual defining mission of a Labour government is acting as the heart to the Tories’ head: expanding the reach and funding of government as a means to promoting equality of outcome and social justice. But what does a Labour government do when there’s no money to spend? 15 years ago, chief secretary to the treasury Liam Byrne infamously left a note to his successor saying ‘Dear Chief Secretary, I'm afraid there is no money. Kind regards – and good luck!’

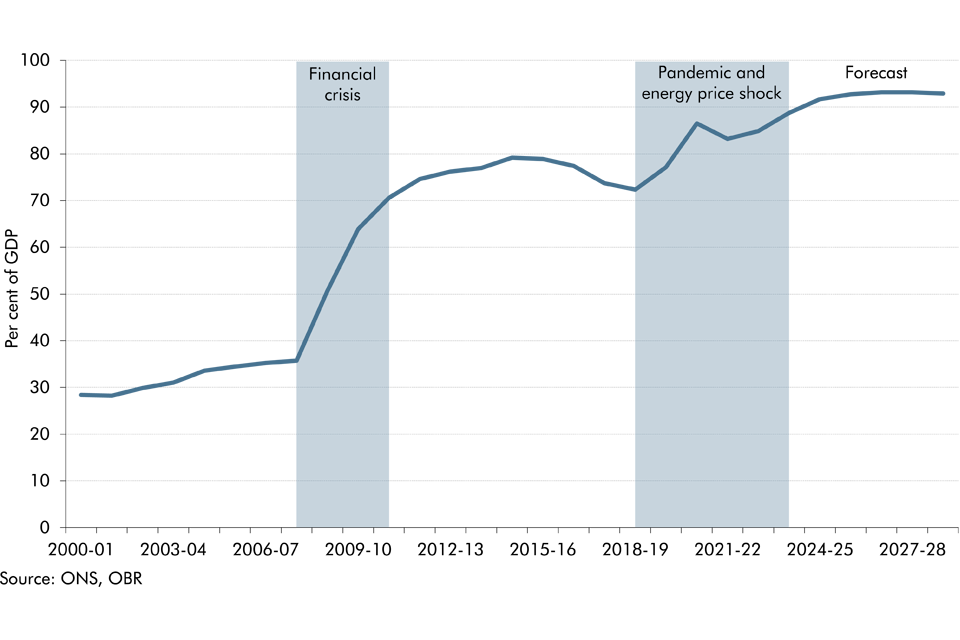

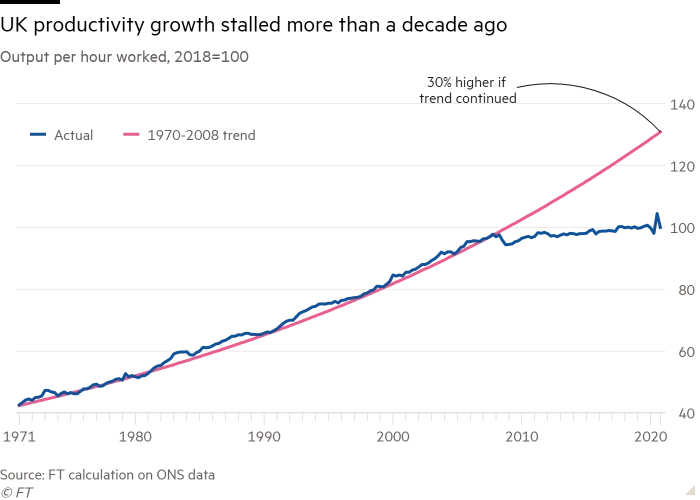

A decade and a half on, and there’s even less than no money left. The debt-to-GDP ratio has grown from under 40 per cent to nearly 100 per cent since that ill-advised letter was written. Economic growth – the once dependable escape valve for state debt – is no longer something British governments can rely on, with per capita growth remaining stagnant since the mid-2000s. Britain’s ageing demographic profile is strong-arming the state into allocating an ever greater proportion of its spending towards age-stratified benefits and health and social care – catering for both the genuine needs, and the wants, of a powerful boomer voter bloc.

Brexit dominated the political agenda from 2016 until 2019, raising trade barriers, but more importantly, distracting politics from the pre-existing and growing crisis in economic growth and living standards. Then there are the external shocks – appearing one after the other, as if arriving by conveyor belt. First there was the Global Financial Crisis. Then Covid-19 saw government spend vast sums on pausing the economy, and paying out furlough cash to the suspended workforce.

Then there was the inflation that followed the Russian invasion of Ukraine, and Liz Truss’s government subsidy towards household energy bills. Yet again: more debt, and with each uptick in debt to GDP, less future room for manoeuvre. The war in Ukraine has also presented a fresh, unavoidable requirement for more spending – this time for raising the defence budget. In an uncertain, multipolar world with a protectionist United States, economic security is once again a means to defensive security. And now, look who’s back in the White House, declaring tariff wars on allied nations.

Growth has not been this difficult to manifest since before the Industrial Revolution, but manifesting it has rarely, if ever, been more important. By circumstance, Labour has been forced to examine an area of politics, philosophy and economics that does not naturally set its loins ablaze. But what does a social democratic party do in government if it cannot increase government spending and expand the reach of government?

Under a social democratic paradigm, there are few means to social justice delivered by the state without more money. And without social justice, what is the point of being in government as a party of the centre left? Labour has come to realise that, as important as growth is for living standards and for the sustainability of the British state, it’s also now an essential precursor to Labour being able to be, well, Labour.

The incentives in the politics of growth have inverted. Long gone is the Tory lust for vigorous and spunky urbanite free enterprise, forsaken for the limp and sedentary comfort of retired suburbia. Boris Johnson said it best: ‘fuck business’ - there’s a new socio-cultural priority in town for Conservatives. Strangely, Labour now finds itself as the party with the biggest immediate incentive to boost growth. Their working-age voter coalition is crying out for affordable housing, better-paid jobs, and cheaper electricity and childcare. All of this points towards a need for growth and what might enable it.

Theory of growth

It’s no secret that the first six months of this Labour government were disappointingly dysfunctional and directionless. Much of this is attributed to operations under Starmer’s departed chief of staff, Sue Gray – but not enough is attributed to how the 2024 election was a wide open goal for Labour, after the Cornbynite disaster of 2019. The atrophy of Conservative competence and ideology offered a far less planned and intellectual route to government than when Labour last re-entered government in 1997.

Neil Kinnock, John Smith, Sir Tony Blair and Gordon Brown had spent more than a decade slowly, but determinedly winning the arguments about what was necessary to accept, and what could be unpicked from the Thatcher-Major political settlement. Starmer had four years to do more than a decade’s worth of work in making the Labour Party electable again – on top of developing a workable, politically palatable theory of what was wrong with Britain, and how it could be fixed.

Except he didn’t, because the first few years of his leadership were devoted to purging the hard left from the party and its power structures, and the pseudopolitics of the Covid-19 response. It was over this time that the cultural and political influence of right-leaning and Labour-hostile newspaper media landscape really started to haemorrhage towards social media newsfeeds and podcasts. And after 2023, all Labour needed to say were the magic words ‘Liz Truss’ to win an argument on the economy. Labour has never had it so good when talking about government finances and the economy.

In short, the party was given the media and political space to be lazy on its theory of growth, the economy and government finances – and didn’t have much time to develop one even if it had been pressed. We see the political consequences today in the indecision and inchoate growth policy that is, let us not forget, the stated ‘defining mission' of this government.

But ‘what is Labour’s theory of growth?’ Ben Ansell posed this seemingly basic, but very insightful question a few months back. We still don’t have an assured answer – let alone one that is communicated ad nauseum to hammer home the message and give a sense of government drive and direction to frontbenchers, activists and voters. The Labour leadership risks stating that growth is its defining mission – without backing it up with coherent, comprehensive and urgent action.

Lord Finkelstein regularly proposes on The Times’ How to Win an Election that boiled down to their essence, there are only three types of election propositions1:

It’s time for a change (1997, 1979, 2010, 2024)

Britain is on track – don’t turn back (2001, 2005, 2015, 1987, 1983)

Better the devil you know (1992, 2019)

If Labour is to win the next election, it must be in the position to claim the second narrative, and be able to say ‘let’s finish the job’ – having made noticeable, if incomplete progress on the economy, public services and stagnant living standards. Anything less will have been a continuation of the last 14 years of Conservative growth, living standards and state services failure.

The unbeatable bomb

Artificial intelligence (AI) could be the government’s single biggest lever to deliver its five missions, especially the goal of kickstarting broad-based economic growth. It is hard to imagine how we will meet the ambition for highest sustained growth in the G7 - and the countless quality-of-life benefits that flow from that - without embracing the opportunities of AI. - Peter Kyle, Secretary of State for Science, Innovation and Technology

Kyle is not in charge of government growth strategy, but it is concerning that cabinet members are apparently going off piste by talking about AI being the ‘government’s single biggest lever,’ for growth, rather than planning reform. Noting the watered-down government aim of achieving the highest sustained growth rate in the G7, Kyle seems to imagine that no other country in the G7 will be trying to achieve exactly the same from shared AI technologies. We are not a walled garden. Differentiation in strategy and regulation may move the dial. The human capital of the UK might move the dial too. But what will differentiate the UK to enable AI-driven top-of-the-G7 growth that wont be pursued by our peer nations?

It’s effortlessly easy to assume that AI is the new beam engine, the new steel blast furnace, the new motor vehicle, the new Haber process – the latest change in technology that drives ongoing productivity growth. But if information technology gains so inexorably led to improvements in productivity growth above baseline, why did the 1980s-2000s telecoms revolution not raise growth above trend rates? Can you spot when emails and digital word processing changed the workplace for ever on the productivity growth chart? Why should we assume that recent developments in AI will lift the growth trajectory from its early noughties dog leg?

But it seems that Starmer is equally bought into the potential for AI to transform both economic growth and government service provision. Recently announcing the use of a new AI tool aimed at speeding up the planning process, he said: ‘For too long, our outdated planning system has held back our country— slowing down the development of vital infrastructure and making it harder to get the homes we need built.’ So far, so good.

‘We’re harnessing the power of AI to help planning officers cut red tape, speed up decisions, and unlock the new homes for hard-working people,’ Starmer added. Let’s be real: the purpose of the system is what it does (often know by its acronym, POSIWID). As Stafford Beer put it, there is ‘no point in claiming that the purpose of a system is to do what it constantly fails to do. That is to say, planning the building homes to meet the needs of the country, its businesses or communities is not the current purpose of our regulatory planning system. Its purpose is to prevent homes being built where it might inconvenience or affront local, extant homeowners. The government claims:

For the first time, this cutting-edge technology will help councils convert decades-old, handwritten planning documents and maps into data in minutes – and will power new types of planning software to slash the 250,000 estimated hours spent by planning officers each year manually checking these documents. This will dramatically reduce delays that have long plagued the system.

Great – but. The United States once developed the unbeatable bomb. Unfortunately, Soviet spies read the plans, and they got the bomb not long after. Likewise, the strategic advantage to the government from using AI in planning will be transitory, at best. The other side is already looking at using AI to counter and automate objections to planning proposals, as James O’Malley surfaced in his recent Substack post. He noted the example of ObjectNow, which apparently offers various paid tiers of service for using AI to automate planning proposal objections. Their website states:

At ObjectNow, we harness the power of artificial intelligence to help campaign groups, communities, and individuals effectively object to large-scale wind farms, solar parks, and battery energy storage systems (BESS) developments. With planning applications becoming increasingly complex, our AI-driven platform simplifies the process, ensuring well-researched, structured, and impactful objections that stand up to scrutiny.

ObjectNow automates the creation of tailored objection letters, integrates relevant policies and environmental concerns, and provides expert guidance to strengthen opposition efforts. Whether you’re facing a single development or a wave of applications in your area, our technology equips you with the tools to respond quickly, accurately, and with maximum impact.

Once again, by far the biggest growth lever that the government has is cutting through the Gordian knot of our planning laws, which constrain the supply of housing and infrastructure. AI will not prevent the system defaulting back towards its unspoken, but evident purpose. It will simply result in more efficient processing of an ever greater volume of content, while not solving for the core political conflict itself.

What large language model (LLMs) and the telecoms technologies of the late 20th century share is a lower effort threshold for the mass sharing and consumption of information. Do we risk, instead of dissolving the inefficiencies of our systems, actively giving more breathing space and capacity to inherently dysfunctional structures? A fundamentally broken incentive system is failure of politics more than a failure of operations. We could be creating a grey-goo government of AI assistants and tools analysing data to death and chatting to each other with little decisive, productive output.

Tech cannot trump politics

AI LLMs are already fully commoditised, with private subscriptions to premium LLM services costing around $20 per month. Other AI applications have near-instantly become as transformative as they are affordable. Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella said in January: ‘As AI gets more efficient and accessible, we will see its use skyrocket, turning it into a commodity we just can't get enough of.’

He’s right to call upon the wisdom of 19th century Liverpudlian economist William Stanley Jevons, who noted the tendency of technology to be used more, not less, the cheaper and more efficient it becomes – rather than seeing total usage decline as efficiency gains mount.

It is wholly a confusion of ideas to suppose that the economical use of fuel is equivalent to a diminished consumption. The very contrary is the truth. Whatever, therefore, conduces to increase the efficiency of coal, and to diminish the cost of its use, directly tends to augment the value of the steam-engine, and to enlarge the field of its operations.

One of the best examples of the so-called Jevons Paradox is the electric light bulb. The cost of producing artificial lighting has dropped by a factor of one thousand since 1850, but despite this, our energy consumption for the purpose of artificial lighting continued to increase in the long run, rather than fall.

The Las Vegas Sphere, an entertainment venue covered in 1.2 million LEDs, represents ‘our seemingly insatiable appetite for stuff,’ said Ed Conway in a New York Times guest essay last year. The lesson is: as technology becomes cheaper, we find new uses for it that were once impractical or uneconomical, rather than cutting back on total input costs. AI is already ubiquitous across government, and it will continue to course through the veins of Whitehall with unrelenting inevitability. But government currently isn’t working. Giving a temporary respite to broken processes and politics is not temporary salvation – it is a monkey’s paw curse.

The Vegas Sphere represents a vulgar usage of lighting technology that could not have been imagined in Thomas Edison’s lab, when energy and bulb-fabrication costs were much higher. Not that the innovation it represents mattered in London, because of politics – in January 2024, the UK government sided with Mayor Sir Sadiq Khan in rejecting a proposed equivalent Sphere in Stratford. MSG Entertainment said at the time:

‘After spending millions of pounds acquiring our site in Stratford and collaboratively engaging in a five-year planning process with numerous governmental bodies, including the local planning authority who approved our plans following careful review, we cannot continue to participate in a process that is merely a political football between rival parties.’

It doesn’t matter how innovative any technology or AI tool is when it faces a broken political process. Even if the Sphere is truly not to society’s taste, there is far too much banned, unrealised economic activity in housing, infrastructure and business parks that gets rejected. These rejections do not happen because the planning process cannot be facilitated without technological advances, or AI enhancements, but because of a political disagreement over what outcomes should be prioritised for society-at-large.

Incidentally, another entertainment Sphere is actually being built – in Abu Dhabi. London turned away the $2bn ultra-venue. Abu Dhabi grabbed it. The problem isn’t technology or innovation — it’s politics. AI does not, and cannot solve for the political human and communitarian disagreements between that which facilitates growth, and its objectors.

Labour must realise that growth is a choice. It is a choice that we are not making. We must cut through the Gordian knot, rather than use AI to try to disentangle it. We must find the route to answering the core political dispute between pro-growth and anti-growth interests. It is only by solving for the dispute in interests that we will resolve our growth crisis – which unlocks the crises in state capacity, living standards, housing and wages. And the sooner that Labour realises it, the sooner it can get on with fixing Britain, and defining the framing for how it wins the next election.

The election years I’ve added here as exemplars of each election theme are my own categorisations.

A Twillock?