How did the Conservatives end up here?

Kier Starmer might fall into the same trap

The politician who wasn’t political

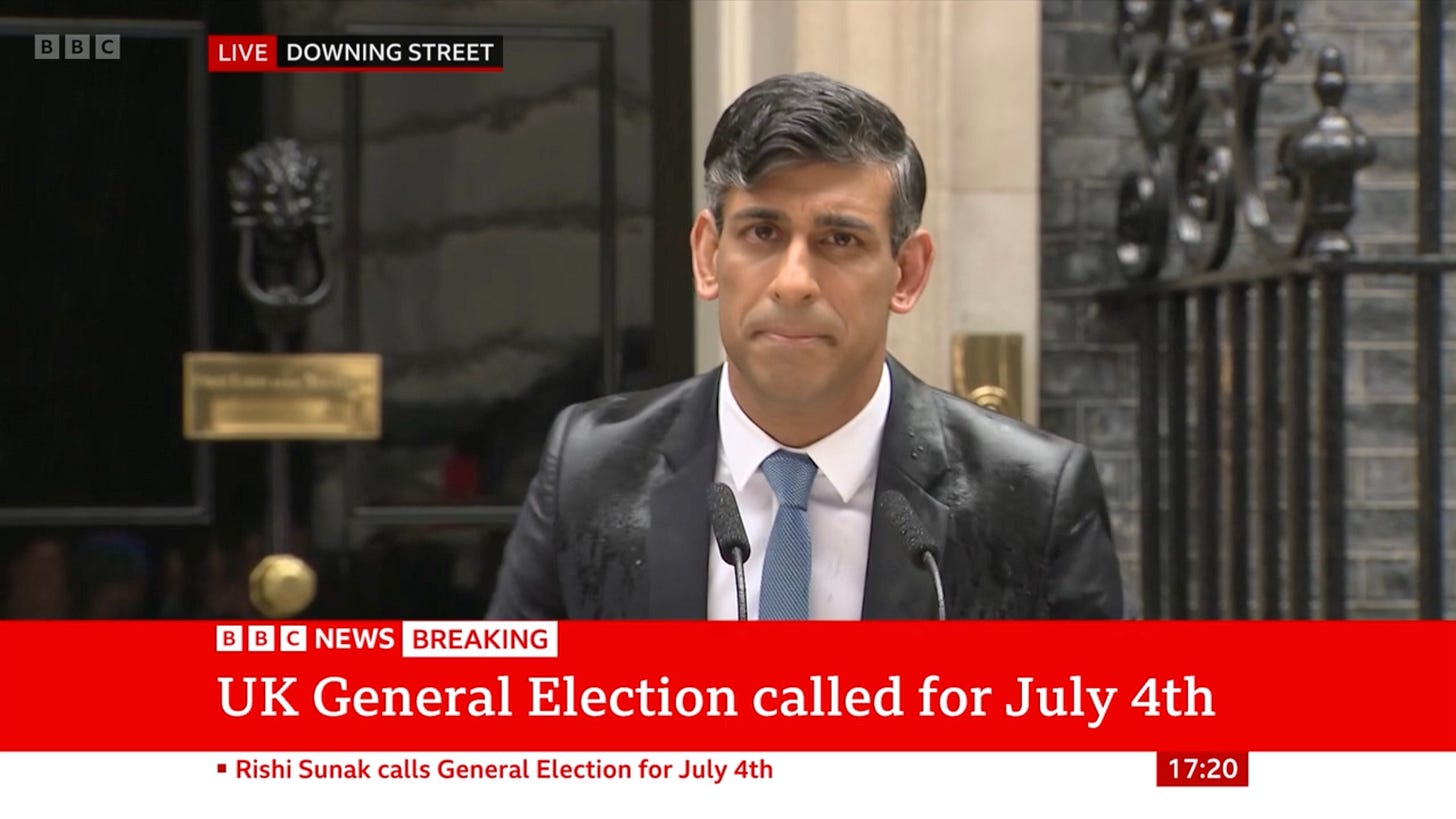

There are many ways of reacting to imminent danger: run away from the problem in the hope it never catches you (Theresa May), make yourself big to give the illusion that you’re more substantial than you actually are (Boris Johnson), chaotically scream and shout to scare it off (Liz Truss). Or you can roll over and play dead (Rishi Sunak).

Sunak is failing. On just about every measure — the economy, housing, policing and justice, NHS waiting lists, illegal and legal migration, local government, and, of course, the polls. It’s not just failure on the opposition’s terms either — it’s on his own and his own party’s terms. There will be no triumphant valedictory speech in the style of Gordon Brown setting out the achievements of New Labour.

It’s like Sunak has given up, going early just to end it all. None of them wants these outcomes — no wonder they’re fighting like rats in a sack. This wasn’t meant to be what happened to the Conservatives’ Golden Boy.

Hastily thrusting the prime ministerial baton into Sunak’s hand after Liz Truss was meant to herald the return of the Sensibles™ to government. Gentle, purposeful, middle-of-the-road government — the sort that keeps the suburbs and the shires sanguine and subdued. If the Sensibles™ had a pitch for how to run government, it wasn’t ideological. It could be summed up in a single word: ‘competence.’

And yet here we are, with Sunak slipping on every banana peel and standing on every rake while his own colleagues thrust custard pies at his face. It’s cruel to laugh, but there’s much schadenfreude to be found in watching the irritatingly perfect prefect trip over his laces. All this despite Sunak’s genuinely impressive CV, backed by collegiate soliloquies to his talents from fellow parliamentarians, praising his intelligence, work ethic and commitment to being well-briefed.

Political journalist have chronicled plenty of Sunak’s political failings, notably the BBC’s Laura Kuenssberg:

‘The most successful politicians at the very top level are the ones who have very strong beliefs and instincts – his approach looks like a series of transactions or problems to be solved,’ a former official who admires Sunak told me.

Another source who worked closely with him said: ‘He thinks that working really hard and being good is enough. Being PM is art, not science - and he is no artist.’

‘We’re like a government of civil servants,’ a serving minister tells me.

And Tim Shipman of The Times:

One recounted the moment the prime minister railed against the prospect of leading his party into its worst general election defeat by complaining about voters and his MPs: ‘Why do people not realise that I’m right?’

A second senior Tory with close links to Downing Street, said: ‘He’s really miserable and that is infecting everyone else. He feels completely snookered.

‘This is like nothing that he’s ever experienced in his life. He’s questioning his own judgment, can’t take a decision, but at the same time doesn’t want to take advice. He’s rude and dismissive to his team for not being good enough. It’s very Gordon Brown: the micromanagement, immersed in details, dithering, blaming others. He and his team have realised they aren’t just going to lose, they are going to get hammered.’

Bizarrely, prime minister Sunak is insufficiently political for politics, without the ability paint a comprehensive and coherent philosophy for government in broad brush strokes and use it to rally troops to a cause, as Dominic Cummings picked up on in August last year:

He spends his time wading through endless detail and spreadsheets on fifth order matters because it’s psychologically easier than doing the PM’s actual job which he doesn’t know how to do nor wants to do.

Officials obviously prefer him to Boris or Truss. He reads the papers diligently and is neither a crook nor a cretin. But the old hands know it’s roughly the Brown failure mode: a workaholic, the PM’s office a massive bottleneck and can’t sustain focus when the news shifts, the smartest MP but can’t build a team or lead etc etc.

No10 is so politically lost that OFFICIALS suggest ways the PM can achieve his priorities faster and his OWN SPADS say ‘no too aggressive’. The fundamental reason for the boats failure is choices by the PM’s political team and a reluctance by Sunak to face unpleasant reality, not deep state resistance.

Sunak’s policy announcements have been an incohesive hodge-podge of whatever takes his fancy. What links the cancellation of HS2, a ban on smoking for anyone born after 2009, national service for teenagers and new qualifications standards1? It’s like he’s gone to the supermarket and bought one third of the ingredients for 5 different meals. Individually, each ingredient might sound delicious, but who wants to eat a Stilton, salmon and marmalade pie?

Politics on hard mode

But Sunak’s biggest failure is diagnostic, not political — it’s his complete failure to identify and grasp the scale and importance of the United Kingdom’s biggest problem — and to build a case to his party and the country that it needs to be sorted. The disaster in question is no longer being obscured by Brexit or Covid-19. It’s a crisis that’s only starting to be talked about seriously in the past few years, and even then, usually only by nerds and wonks.

The crisis is this: Britain has barely seen any productivity growth since before the 2008 financial crisis. Our average worker is not much more productive today than they were nearly two decades ago.

And because most (though not all) economic growth is dependent on productivity growth, the trend in British GDP per capita and productivity growth is the same — dead since around or just before the Global Financial Crisis.

This is not just a temporary phenomenon that we should be relaxed and sedate about — a productivity growth trend that extends all the way back to the Industrial Revolution ended nearly 20 years ago, and with it the bountiful and succulent fruits that it offered.

Nearly all of Sunak’s challenges are downstream of this fundamental fact. Because wages and per capita GDP are tied to productivity growth, living standards are stagnating — and that’s just in aggregate.

Put stagnant incomes next to rapidly inflating asset prices, and for younger people, there is an active decline in age-equivalent living standards versus previous generations (measured by wealth accumulation and housing quality and floorspace consumption.) All this despite huge advances in technology and increases in total human wealth. It should not surprise us that our politics has become so volatile under these conditions.

Negligible productivity growth also means we can no longer finance state spending by anticipating economic growth and therefore assuming that future tax receipts will grow organically. In a healthy economy, the growth you can forecast for tomorrow ensures you can spend more money responsibly today without increasing the deficit or debt as a percentage of GDP, like a business investing in a new machine in the expectation it will pay itself off in the future.

If British productivity growth has ended permanently, this leaves us with two options: cut the state coat according to the state’s cloth, or raise taxation beyond the highest level since the Second World War to keep our spending tastes sustainable.

Instead we are doing a chaotic combination of the two, where government tries to do the full scope what it did a decade ago, but on increasingly stretched budgets, despite rising taxes. Our expectations of the state have only increased, while our ability to finance it has decreased.

Demographics are adding to this pressure — a very large cohort of people is moving into old age, and combined with longer post retirement longevity, we are going to see demand continue to increase for state spending on health and social care, and pensions in the coming decades. Without productivity growth, how can we fund our expectations of the state?

The end of productivity growth is not inevitable, as the United States demonstrates, both by having a higher level of productivity than the UK, which we could catch up to by adopting American innovations, and by still growing today, even from a higher base. There is still fruit to be picked higher in the tree.

We need to understand that stagnant productivity growth is the midwife of stagnant wages, stagnant or declining living standards, stagnant tax revenues and stagnant or declining public services. It is the midwife of growing NHS waitlists, of the increasing number of potholes on your commute, and of the security tags on cheddar cheese in Tesco that you didn’t see a few years ago.

This is not just for the politics of the entrepreneurial right — productivity growth is the most effective means to deliver social justice through making the poor wealthier. Productivity growth should be the most urgent priority of left wingers looking to see living standards and public services improve for deprived communities and individuals.

We’ve had a few centuries of politics on easy mode, where growth provided an expanding tax base to fund public service expectations and push up real incomes. Now we’re experiencing politics on hard mode, with no easy choices to be made anywhere. Instead of baking more bread, we are rationing the loaves we have.

This worked for the Tory party for a while, with low interest rates supporting the household incomes and consumer spending of the boomer cohort that the Conservatives have become so dependent on.

But stagnant productivity growth has put paid to that, killing off the future voter base and squeezing the funding of public services that boomers are becoming increasingly reliant on as they age into healthcare needs. Not even the boomers can be satisfied any longer. Wile E. Coyote has discovered he’s not running on solid ground any more.

The end of productivity growth is also partly responsible for the chaos we’ve seen in the Conservative Party for nearly a decade, calling the curtain on the intergenerational voting coalition and dissolving the glue that bound MPs of disparate, but sufficiently compatible values and tastes together under one flag.

Without a crisis, electoral success or growing living standards and a stable, secure state with adequate funding for boomer health and social care to unite around, the incentives to remain collegiate and helpful have faded away.

Downstream focus, upstream cause

It is the nature of politics and media that we focus our attention on the digestible and eye-catching human interest stories that are downstream products of the cessation of productivity growth. A 15 hour wait for an ambulance or crumbling school buildings caused by government services with squeezed funding are much easier concepts to understand and communicate than theories covering the ultimate, upstream cause of constricted budgets.

Whatever the actual apportionment of blame for the end of British productivity growth actually is, there is one very big likely culprit, which if we solved, would also deliver a great deal of social justice regardless. You guessed it — the difficulty, complexity and cost of building homes and infrastructure is Himbonomics’ biggest productivity villain.

Making homes and infrastructure very expensive and difficult to build has upended all of the incetive structures that once favoured growth. Why bother with the fight and cost of installing better power lines with more capacity when local residents are ‘in despair’ over the provision of utilities infrastructure?

Want to buy a new home near to a good job? Sorry, the barely perceptible view of a church through a small gap in some trees is more important than the construction of a new apartment building 15 miles away.

Want to construct a film studio in a disused quarry next to a busy dual carriageway? Local Tory candidate Joy Morrissey has successfully campaigned against such distasteful jobs and economic activity: ‘I urge the applicants to now recognise, once and for all, this is the wrong development in the wrong location.’ She was backed by her Liberal Democrat rival, Anna Crabtree, who said that the development ‘could not be justified economically,’ which must have come as a surprise to the private businesses who were applying to invest in the site for their own economic reasons.

Want to build hyperscale data centres on a former landfill site, five miles from Heathrow airport to support the cloud infrastructure of tomorrow? Unfortunately the economic case does not ‘outweigh the harm to the Green Belt and to the character and appearance of the [former landfill],’ according to self-proclaimed YIMBY housing secretary, Michael Gove.

This is the core failure of Sunak and the wider Conservative Party over its 14 years in power. Not Brexit, not the management of the state itself — though few will argue it’s done well on either — but the complete lack of insight into why the country is where it is. We haven’t lost the means to productivity growth — the ‘free market’ Tory party banned it instead.

It may well be the only strategy that the party has left, but it is astonishing seeing it steer into, rather than out of its strategic mistake of prioritising elderly, NIMBY homeowners above all else during the campaign so far.

Yes — making the argument on housing and infrastructure to your voters, candidates and activists is hard. It means challenging them with complicated and difficult truths that they may be unwilling to hear. But if you’re an activist, parliamentary candidate, or instinctive Conservative supporter worried about this challenge, ask yourself: how much are you enjoying it right now? Is this working? Is it worth it?

From a distance it seems more likely that the Tories will go fully off the deep end during and after the election, chasing ungrateful and rambunctious Reform voters with reactive, reactionist policies. They will spend time armour-plating the areas on the planes that return home with bullet holes like proposing national service, not realising that we need to patch the areas critical for all planes to come home like economic growth, housing affordability and working, sustainable state services.

Even with the party heading for a catastrophic loss, it has barely even begun to make the first steps on the journey towards accepting this truth. It cannot be overstated how unintellectual the Conservative Party’s natural instincts are. While some groups like Next Gen Tories are making the thinking case, the wider party is probably a decade behind the Canadian Conservatives.

Pierre Poilievre’s Canuck Tories have come to understand that protecting the veto power of homeowners above all else has consequences for conservatives and Conservatives, from reduced family formation to the growth of the state and higher welfare expectations, to a diminished natural voter base with wealth and family to protect.

But it’s much easier to campaign on this from opposition, than reform it from government. Starmer will soon walk through the door of Number 10, facing a comparable, but much worse set of problems. The instinct of Labour in government will be to spend more money, but it won’t have any to begin with, unlike in 1997.

The Labour trap

Kier Starmer’s Labour Party seems to have the right instincts on understanding how important bringing back growth is for its core mission of social justice. They realise that they will need to do something big to find the money to fund and reform public services — and have linked this to building more homes and infrastructure (which also delivers social justice in of itself.)

But there is still too much of a reliance on recycled policy ‘solutions’ that have had a marginal (albeit sometimes positive) impact on housing and infrastructure supply, such as New Towns. We should note that despite several iterations of New Towns, housing affordability criteria and demand-side subsidy, we still have a housing crisis that is getting worse, not better.

This is because the incentive structures that facilitate our housing and infrastructure outcomes have not been comprehensively reformed since the the Town and Country Planning Act 1947.

The history of attempts to reform planning in Britain is proof that political willpower is not enough: you need to be smart, not just brave — Samuel Watling, Works in Progress.

Housing tenure is dominated by owner-occupiers. They are more likely to be older, more likely to vote, more likely to live in a swing seat, and to be highly motivated concerning changes in their immediate surrounds. As the Triumph of Janet described, they have little incentive to back development in their backyard, and plenty of incentive to block it and vote against it.

There is enough political will in the Labour party right now to do something big on housing, particularly if — as the polls indicate — Starmer enters Number 10 with a large majority. Perhaps he can even get a few New Towns through before the old structural pressures against development start to re-assert themselves.

But does he want to be the Prime Minister that made a small dent in housing, like his predecessors, or actually slay the planning regulation dragon and become a reforming prime minister with a legacy for the history books?

If he wants the latter this will mean a laser focus on restructuring the incentive structures in British planning. How can we make the huge, but widely-distributed costs of blocking infrastructure and housing visible and felt by objectors right now, rather than collectively and hypothetically in the future? How can we make the benefits of approving of and welcoming infrastructure and housing clear to existing owner-occupiers?

Any policy solution that does not focus on the upstream incentive structures will see the dents push themselves back out through population growth, and the re-establishment of the cultural and political power of NIMBYism in an incentive structure that rewards it. A few temporary dents in the planning system will not bring back productivity growth, and without this and the living standards improvements and tax revenue it would generate, Labour can kiss the rest of its ambitions for government goodbye.

Starmer will have limited time to get any of this right. The demands on any prime minister are immense — never more so than in a period of constrained budgets and dilapidated public services with high expectations coming from all directions. He could spend his energy and political capital on the downstream management of the consequences of the end of productivity growth.

Or he could be the Labour prime minister that brings Britain back to life, restoring productivity growth by reforming the incentive structures that deliver our harmful planning outcomes. The payoff will take longer. But the fruits of restored income growth and a sustainable tax base for state spending will be so much sweeter. Stay upstream, Keir.

Perhaps the only thing that links these policies is being against the freedoms and living standards of the next generation.

Excellent article! But the reason why Starmer is not going to do any of these things is also in the article: "...does he (Starmer) want to be the Prime Minister that made a small dent in housing, like his predecessors, or actually slay the planning regulation dragon and become a reforming prime minister with a legacy for the history books?"

At the end of the day, he wants to be the Prime minister, no matter the dent kind or the slaying dragon kind. So, he is definitely not going to act against the interests of the people who are "more likely to vote, more likely to live in a swing seat, and to be highly motivated concerning changes in their immediate surrounds." Fix this, growth will follow.

The answer , with all due respect , to your very winded article is explained very simply by zero interest rates since 2008 - or very well explained in the book The Price of Time

Ok so we’ve had a spike recently but the die was cast back in 2008

All economic woes in fact lead from low/zero interest rates

The machine just stops working , it really is that simple

Look at Japan for example